The Shah Ali shrine in Dhaka and mazārs as the scene of ideological and spiritual frictions

Legend has it that the saint Shah Ali Baghdadi lived to a hundred years. Born during the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad, he first arrived in Bengal, in Faridpur, by the Padma River via Delhi, but many of these biographical details reside in the domain of hearsay – though what stands grounded is the eponymous shrine and mosque named after him in Dhaka’s Mirpur, where he lies entombed. As one of the larger mazārs in Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka, in its northern neighbourhood Mirpur – with a formal administrative structure, and an institutional scaffolding which situates it firmly within the neighbourhood’s formal and informal economic, social, and cultural milieu, including a substantial and lucrative landholding – the Shah Ali mazār, popularly known as the Mirpur mazār, commands an imposing presence. But even as a sacred site, its foundation quakes from an epistemological and ecclesiastical1 onslaught against shrines and mausoleums present across Muslim societies. It suffers this for being essentially no different from other ‘typical’ Muslim shrines across South Asia, in its function as a site of both congregation and contestation; serving as a spatial and temporal link for the outmoded and the outcast, as a place of refuge, rest and reflection, for devotees and social castaways alike – and who are we to make that foul distinction? However, that they welcome the latter is a source of consternation to mazār detractors who buttress their position with claims of antisocial activity against shrines. Equally, shrines are a flashpoint for a much more protracted conflict around authenticity (sahih), orthodoxies, and evidence, as they often defy the terms of substantiation as we understand it.2 Mazārs trouble and are troubling because they are out of line, making them more than houses of worship, and into places of social and spiritual discomfort for both Salafi3 or Deobandi4 religious orders, as well as for secular biopolitical orthodoxies. In the eyes of these double orthodoxies, mazārs are unreliable, undisciplined zones of unease and suspicion – impure, unclean, messy – sheltering the wrong kinds of people and knowledge (or to them, what amounts to ‘non-knowledge’, that is, ignorance, or even worse, idolatry, which is tantamount to challenging God).

Using the Shah Ali shrine illustratively, I will argue for a more insurgent understanding and undertaking of mazārs as sanctuaries, which probes the foundational assumptions around the production and politics of suspicion. Beginning with a survey of the Shah Ali shrine, and mazārs in general, I will then offer an account of the spatial, temporal disquiets rooted in specific epistemological and ecclesiastical objections, which render them ill-suited to those specific religious and secular orthodoxies. Charting an historical and cultural trajectory, my aim is to show how this discomfort around mazārs offers a point of entry into shifts of perspective around what we consider ‘reliable’ knowledge, what is ‘unfounded’ or simply superstitious, and of a social space to be ‘cleansed’ of ‘dirty’ subjects. The aim is to reposition mazārs from being thought of as out of place and backward – as a social hindrance, and spatially, temporally out of step – while also avoiding a rarefication of possible contra- and counterpositions – that is, of simplifying and sentimentalising them to the point of inert nostalgia; or stripping them of the complexities amongst which they operate as institutions within prevailing and extractive economic and social relations. As such, I want to offer a defiant stance on disciplined subjects and knowledges, and to see mazārs, with particular consideration of the Shah Ali shrine within Dhaka’s psychogeographic bearings, as housing and displacing systemised categorisations of knowledge and subjects.

Fall from grace? Shrines as a threat to biopolitical governance, new knowledge and disciplinary systems

Despite its storied presence and the presence of devotees and social ‘exiles’ alike bolstering the mazār’s significance in Mirpur’s, and the city’s, social, spiritual, cultural fabric, it is also those multiple presences and their ability to unsettle and undermine disciplinary social frameworks that have made mazārs targets for attack. Detractors condemn these sites for encouraging antisocial behaviours. Both puritan and secular critics fault shrines and shrine-based rituals for what they believe to be flawed and duplicitous undertakings, which they argue are against ‘pure’ and ‘scientific’ knowledge traditions and Islamic teachings. Even historical details surrounding the shrine remain sparse, sporadic, and conflicting. Did Shah Ali pass in 1480 AD, 1507 AD, or 1577 AD? These divergent claims, some almost a century apart, would place him and his arrival in Bengal under different, though associated, historical periods. More seriously, are mazārs, including the Shah Ali shrine, really burial grounds, or are they fabulist confections? This last charge attempts to create an epistemological, temporal, spiritual suspicion that they hold no connection to verifiable truth – no reliable or certified information on who or what lies buried underneath, thereby perpetuating and exploiting superstition – and, a positivist favourite, that they bear no relation to facts. Relying on a literal, staunchly puritan interpretation, Salafi and Deobandi adherents have long disclaimed shrines with accusations of idolatry: to them, shrines accentuate invalid, un-Islamic practices, with a surrounding spiritual, spatial, social landscape that is in contravention of pure Islamic instructions. It is both absence and presence that these critics object to – that the shrines and shrine-centric rituals corrupt ‘pure’ and ‘authentic’ Islamic teachings, contributing to an absence, and that the veneration of the deceased saints are akin to committing shirk,5 because it attributes divine qualities to mortals, a presence of qualities only reserved for God.

Steeped in lessons of European enlightenment, Bengali modernism6 and Bengali Muslim reformers have invoked scientific progress and rationalism as an antidote to regressive – in their characterisation – practices and beliefs of the colonised masses7 who were holding them back from progress. One of the premier intellectuals of Bengali Muslim reformism, Syed Waliullah (1922–1971), authored a now influential novella, Lal Salu (1948), on this very subject, with a fake mullah and his exploits at its centre. Framed as a cautionary tale, Lal Salu explicates one man’s mission to defraud a community of simple, unsuspecting villagers who are easily misguided in the name of religion – in this case Islam – for personal gain. In his introduction to the English translation, Serajul Islam Chowdhury claims that:

In an odd, and somewhat ironical, manner, this village represents Bangladesh in miniature, particularly in respect of poverty and fundamentalism, which in fact go hand in hand, one helping the other here as much as elsewhere. Waliullah’s memorable observation, ‘There are more tupees than heads of cattle, more tupees than sheaves of rice,’ reminds us of an abiding collaboration between poverty and religion. […] The village is almost mythical; it is without connection with the world outside; it has no radio set; no newspaper reaches it; no school exists; even the favorite pastime of the Bengalis called politics is absent. Life here is elemental. Even for backward Bengal such a village is exceptional. (Chowdhury in Waliullah 2022, p. xi)

Chowdhury and Waliullah display an astoundingly churlish presumption about the constitution of a supposedly pastoral ignorance and impoverishment, relying on artless correlations and categories of analysis around religious customs and costumes – for example, their derision of ‘tupees’ (skullcaps worn by Muslim men) and rituals, and the use of terms such as ‘fundamentalism’ and ‘village’. Though there may be many types of fundamentalisms (e.g. market fundamentalism), beginning in the twentieth century, the term has acquired a new meaning, having lost any critical import to now only denote ‘Islamic extremism’, which itself is another politically loaded expression. The conflation of religiosity – particularly Muslim religiosity, rituals, customs, and costumes with extremism and suspicion has a colonial, geopolitical, cultural vintage, and to rely on terms like extremism, which has come to signify and stir panic through its wilful application against Islam and Muslims, is a troubled enterprise. Both Chowdhury and the author Waliullah maintain a schematic view of villages as being sites in the distance, appearing only as instrumental simulacra of a mass disposition where the people, their social life, aesthetic sense, ceremonies, rituals, and cultural ecology are deemed valid or legible when tested against ‘modern’ tastes8 of enlightenment – and where they fail or succeed on those terms. While they themselves may have been from there, and of there, their elevation into the lettered class created an epistemic break, allowing them to issue judgements of false belief and sophistry against the comportment of those lives, the villagers, and their communities from that remove. The particular trajectory of this lettered class in Bengal can explain the subsequent social terrain that is critical of shrines and shrine-based practices as being superstitious.

The Bengali intelligentsia – the majority of whom were from Hindu communities, although some were Muslim – during the British colonial era enthusiastically adopted Western education, were drawn from ‘the middle and lower echelons of the rent-receiving hierarchy’, and a number of them were also descended from families recruited into the colonial bureaucracy, despite retaining ties to their rural and ancestral homes (Chatterji 1994, p. 6) – as was the case with Waliullah, whose father was a district magistrate during British rule. In an essay on translation practices in colonial Bengal, Emily Larocque writes that:

The newest expression of Orientalism in colonial India meant enacting a policy of indirect rule where the indigenous elite were co-opted into ruling with the British, facilitating the government and policies of the colonizer. Education thus became a hugely important tool of encouraging the co-opted indigenous elite to adopt whole-heartedly the British style of governance. (Larocque 2011, p. 34)

This adoption of British education and governance happened to the extent that, along with an increased demand for English texts among the colonially educated class, colonial subjects developed a preference for European translations of Indian texts, meant for a Western readership, because of the prestige attached to them. These texts furnished the ‘educated Indian [with] a whole range of Orientalist images’, resulting in them accessing their ‘own past through the translations and histories circulating through colonial discourse’ (Larocque 2011, p. 35). By that time, English had also replaced Farsi as the bureaucratic and administrative language, and when the colonial office holders encouraged local language, there is evidence that they ‘preferred the type of Bengali that demonstrated more Sanskrit in its origins’ (Larocque 2011, p. 37), thereby fabricating a schism between a questionable idea of authentic, pure, original Bengali, and hybridised Arabic-Farsi-influenced – thus Islamicised – Bengali.

The origin and development of a Bengali middle class – itself a pliable category, which could include lower-ranked colonial officers, a burgeoning professional class, and even a portion of landed gentry, but formed through their participation and recruitment into the colonial administrative structures and educated within that system – are direct results of that British policy. Composed largely of Hindu upper-caste members, the Bengali intelligentsia were drawn mainly from the neo-middle class of that era, and a variety of reformist movements owed their emergence to the newly minted tastes, preferences, social, and cultural outlook of this class initiated into the British colonial and Western system, with lingering caste hierarchies. A distrust of and bias against the primitive customs of their lesser-educated brethren, a significant portion of whom were Muslim peasants, became the foundation of reformist movements taken up by many of these Bengali modernisers.

For their part, religious revivalist and secular Muslim reformers recognised inherent attempts at alienating and othering Islam from a Bengali cultural-linguistic identity,9 and positioned themselves as vanguards of Bengali Muslim or Islamic reformism and awakening in Bengal. Many of these reformers, and the Bengali Muslim intelligentsia, however, framed their charge as one of a journey from darkness – from an adulterated, impure or unscientific and irrational Islamic practice of the locals – to light, towards a more ‘authentic’, pure, scientific and rational Islam. In that, they reproduced and relied on a similar epistemological template as that of their Orientalist, colonial administrator, Bengali Hindu intelligentsia counterparts of the era from the mid- to late nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries.

On the other hand, the formation of ethnic, religious, indigenous and other identities themselves, and the classification of these identities into distinct groups as if to signify separate customs and rituals, followed from the ‘British obsession with classifying the Indian population’ where ‘colonial census was not a passive instrument of data gathering but an active process that created new identity for Indians’, and ‘religion and caste played a central role in [that] colonial imagination because it provided fertile grounds for production of colonial knowledge based on [what purported to be] objective science’ (Abbas 2010, p. 28). A more porous, fluid, conditional process turned into a process of definitive category-making subjected to incipient biopolitical governance, as well as a particular colonial and class politics from which these distinctive identities and subjectivities like Bengali or Bengali Muslim emerged. Because ‘the colonial census was the tool with which the British engineered the social rubric of Indian society. The categories conceived by the censuses in order to define and classify the Indian people impacted their understanding of themselves’ (Abbas 2010, p. 16). A colonial historiography influenced their understandings of histories, cultures, and a past, to recast them into a simplified and primarily religious, Hindu versus Muslim, social, cultural, historical schema, and the various, subsequent (and to this day) anti-colonial, nationalist, ethno- or religious nationalist, secular, religious revivalist movements scarcely escaped the straitjackets of what the historian Romila Thapar calls ‘colonial periodisation’ (Thapar 2002, p. 21). Moreover, from within these communities, battles waged to reformulate a unified, authentic, ahistoric, archetypal idea and ideal of a Hindu or Muslim, their culture, history, and identity at the cost of deliberately ignoring historical and political complexities and contingencies following the British template. Novels like Lal Salu and opposition to shrines are situated within these historical, colonial, political, cultural contexts, with the convergence of ideas between both the religious revivalist, purist Islamic, and secular flanks of reformism.

A crack in the code or continuation? Reconstitution and resignification of shrines

In the ensuing unrest and uncertainty after the popular July–August uprising of 2024, which toppled an authoritarian regime of fifteen years, nearly a hundred mazārs have been attacked and damaged to date in Bangladesh. The more sectarian Salafi and Deobandi strains of Islamic politics of piety and purification have long advocated against shrines across the Muslim world, not just in Bengal or Bangladesh. And alarming as they are in their unfolding against political impunity,10 a continuation connects these developments.

It is impossible to simplify the development of shrine-based rituals and religious pilgrimages in Muslim societies – both of which predate Islam11 – yet one of the five pillars of Islam is the hajj, or pilgrimage. But disputes and differences of interpretation arose around pilgrimage to and devotional practices in tombs of revered figures, since the notion of saints, intermediaries, and clergy are not formalised in Islamic teaching, which emphasises instead direct communion with God. Though singular status is given to the Prophet Muhammad, his mortality, and reminders not to elevate him to the status of divinity, are central tenets of the religion, which teaches that powers of intercession lie with the everyman/woman and not an intermediary. Though the scripture recognises and reserves special place for a pīr, fakir, auliyas (spiritual person, monastic mendicant, friend of God) who may possess extraordinary spiritual insights, neither the Prophet nor the holy men or women could attain sainthood in a formal sense. Nevertheless, across Muslim societies, the veneration of spiritual figures and shrine pilgrimages developed over time. But within the last two hundred years, ‘the confluence of the Salaf movement and the modernization of political and social structures in Muslim countries has severely impaired the practice of shrine visits, even though people still visit them on certain occasions’ (Boissevain 2017, p. 7). The Saudi regime, for example, is well known for its penchant for razing and repaving historical sites with the official claim to dissuading ‘shirk’ and site and saint veneration, and to accommodate the needs of growing cities and centres: ‘Construction works have already transformed Mecca and Medina into cities without a past, dominated by skyscrapers’ (Osser 2015). At its heart, however, the destruction of historical sites is a political and historical revisionist project, that disappears one kind of past to create a new mythos of another past to fit, in the case of Mecca and Medina, Saudi polity, since ‘heritage sites are part of nationalistic identity as well as a channel to create culture and history in the public imagination’ (Ceriter 2022, p. 9).

In South Asia, shrines and pilgrimage rituals developed through a process of absorption and accretion, and in Bengal, as elsewhere, this was complemented by a political, social, spatial recalibration of the Mughal era:

Soon after the Mughal conquest, mosques and shrines began proliferating throughout the Chittagong hinterland. […] Between 1666 and 1760, a total of 288 known tax-free grants in jungle land were given to pioneers by Mughal authorities in Chittagong for the purpose of clearing forests and establishing permanent agricultural settlements. These included grants to trustees of mosques, to trustees of the shrines (dargāhs) of Muslim holy men, to pious Muslims not attached to any such institution, to trustees of Hindu temples, and to Brahman communities. […] The grants thus set in motion important social processes in this part of the delta: forest lands became rice fields. (Eaton 1993, p. 238-239)

Miscellaneous territory

Though both mosques and shrines are social spaces, and despite the heterogeneity of shrines and tombs across the Islamic world, and that royal approval and administrative support by the Mughals in South Asia did not mean that all shrines acquired the same standing or significance as the one in Ajmer, shrines have traditionally been the more welcoming spaces, hosting people from across classes, faiths, and orientations. As places of retreat, refuge, contemplation, as well as ecstatic communion with the divine, they evolved parallel to the more regimented sacred spaces and geographies of mosques and temples. As Henri Lefebvre argued, the very notion of social spaces resists analysis, yet nonetheless contains dimensions of human relations, including that of production and social reproduction; more importantly, they are not neutral, with each enacting power relations within which they are located, but can still accommodate underground or clandestine aspects (Lefebvre 1992, p. 33). In shrines more than other sacred or social spaces, an idea of a commons could be realised, and more permissive practices flourished.

Because shrines operate as otherwise zones relative to other social spaces, distanced from logics of control more prevalent in spatial configurations of colonial and later modern nation states, they are targets of regulation through disciplinary governance. Since they have not historically or typically restricted or monitored entry and gatherings,17 and have allowed resting, socialising, loitering, rituals using music, dance and intoxicants, providing space for the ostracised, the insane,18 and the unhoused, mazārs appear intolerable to the social, cultural, aesthetic, political preferences of a polity, both religious and secular, groomed under colonial tutelage and invested in a controlled citizenry and subjecthood.19 That mazārs can give licence and permission for pleasure and rest, ritual or casual use of intoxicants, puts them at a remove from notions of legitimacy, legality, purity, and respectability held by the arbiters of colonial and then nation states, but once again, their rejection is rooted in the tendencies and political imperatives of each. The British amassed hefty profits from the opium trade as it simultaneously disciplined the intoxication practices of Muslim and Hindu spiritual figures via a regime of classification, criminalisation, vilification, and exclusion; and both colonial administrators and their social counterparts, like missionaries, ‘tightened control over intransigent social categories like Faqirs and Sanyasis’ (Zami 2015, p. 231). Later, narrative and policy prescriptions from the American war on drugs would influence and dominate social understandings of drug use and criminality in Bangladesh,20 further adding to shrine delegitimisation campaigns. Spatially out of step, ambiguous, and out of bounds, mazārs are a break from and threat to the all-consuming impulses of biopolitical discipline and surveillance, which is precisely why they seem destabilising to that status quo, and are threatened.

Every Ramadan, the Shah Ali shrine arranges sehri and iftar for the unfed and marginalised, without discriminating on the basis of religion. These are attended by neighbourhood locals and others who travel from a distance. In a city starved for open, public and social spaces, and overtaken by capitalist and surveilled enclosures, the shrine’s square can be a sanctuary – allowing unbidden socialities at all times, unhurried ruminations, satisfying a heart’s pulls, a stomach’s tugs, a search for pause and recline. On a visit there, a man showed me his rings and henna designs on his hands, gifts from and a tribute to lovers and friends. Nearby, another man fiddled with a pink, old, battered analogue phone to scroll and find a favourite musical number.21 Further afield, a woman sat guarding a single chicken donated that day. Each of them defied the expectations of operating within an efficient, productive, controlled social, spatial, and temporal framework.

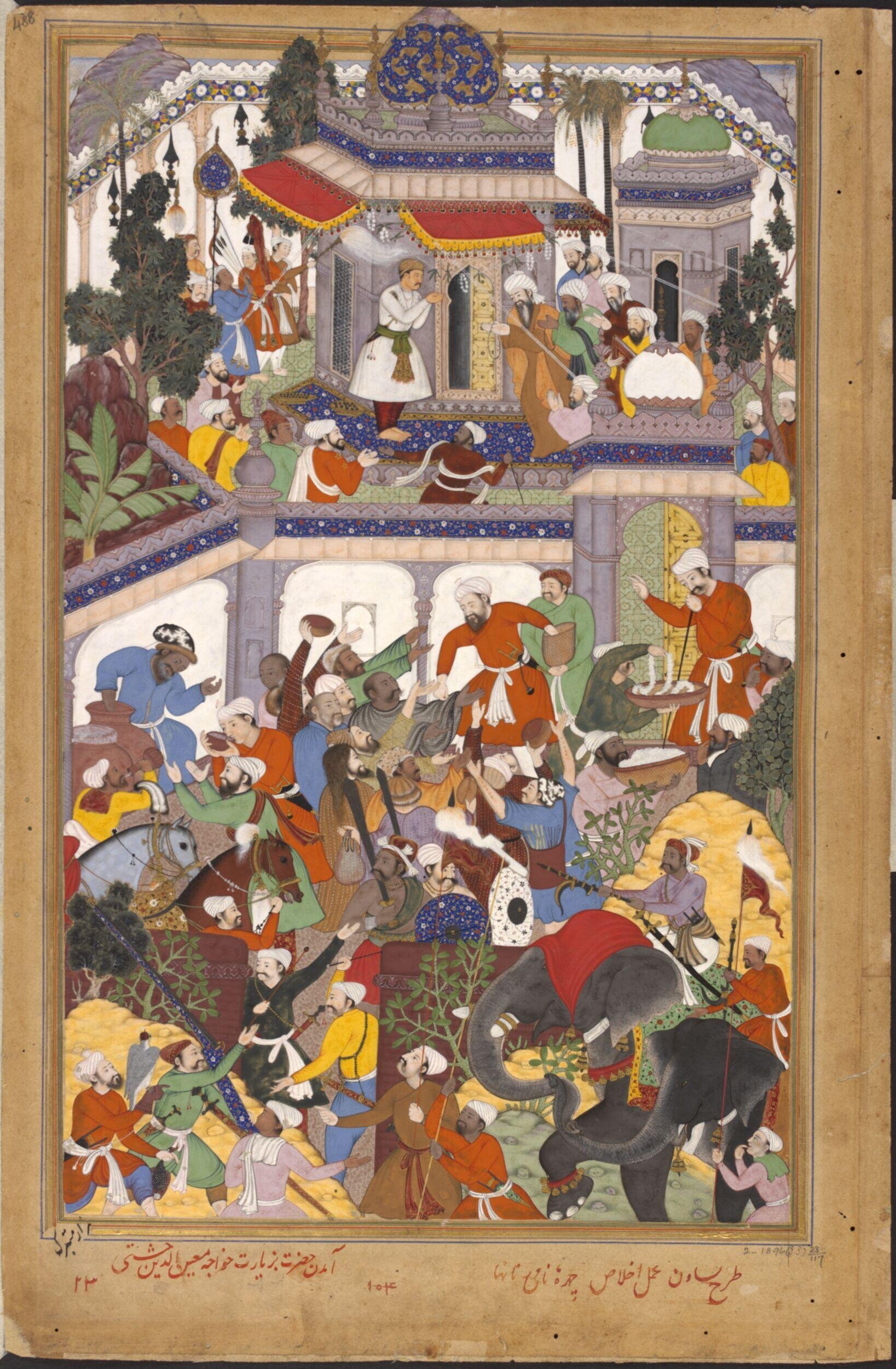

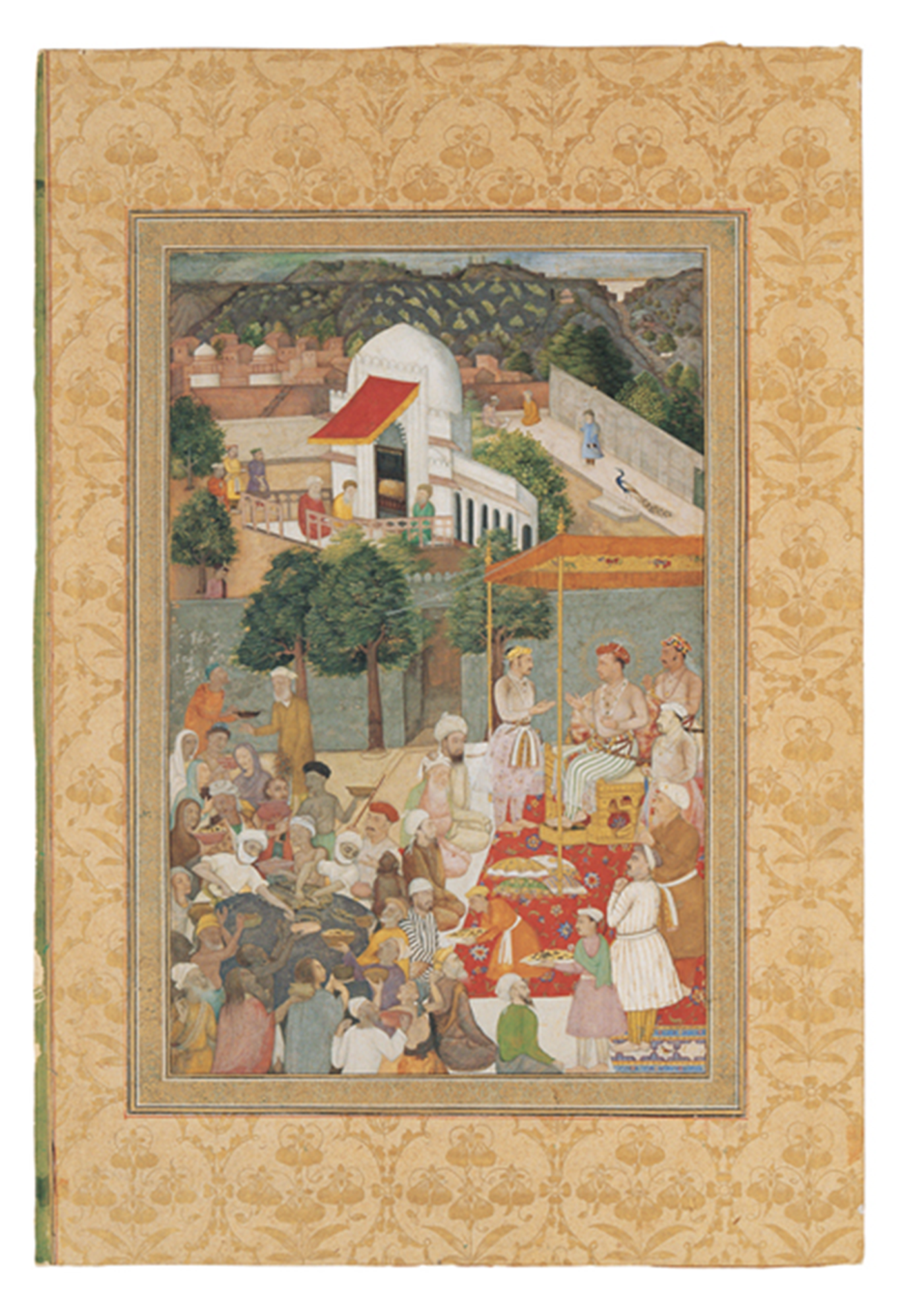

In the two paintings discussed earlier (Figures. 2 and 3), seeking and giving suffuse the royal visits to the shrine, with action and transaction taking precedence – the distribution and consumption of food and beverages, sale of flowers, banter, conversation, devotion, and, above all, both a sense of ceremony and ease. They give a sense of the heterogeneous space and activity also present in the Shah Ali shrine. In the Lefebvrian sense, the mazār isn’t without power relations and prevailing institutional mechanisms and codifications – with a governing body, a police box in one corner of its sprawling premises, and a decision taken several years ago to limit music and dance in response to creeping antagonisms. But in the same sense and more than in any other site (e.g. families, workplaces, educational institutions), it can still evade and provide for clandestine and undefined/undisciplined subjectivities, and deliver comfort to social outcasts. In its ability to create and produce categorical confusions – blurring between socially acceptable and criminalised, psychogeographic slips, territorial porosity, and time spent without limits – the Shah Ali shrine stands askance to the ID-ed22 measures of our social, public, and private lives.

Mazārs as sites of temporal, spatial, epistemological slippage

Mazārs like Shah Ali are stations of social, shared, yet partially anonymous – be they transient or regular – interactions which cannot be fully recorded, captured, or documented. A candle is lit and burns in faith, moments and mementos permutate, shedding or acquiring meaning, afternoon visits are made to find shade from the sun; there is love, there is freedom, there is exhaustion; steps as seats, multitudinous congregations, hope for deliverance or a meal, hands raised like Akbar. Not fully definable, its status draws from the collective, scattered tangle of reciprocities it generates. Very little is recorded or verifiable about the shrine, and it may have been abandoned and dilapidated for a period of time before being revived as a sacred site. What matters are not the details, but generative and generational diegetic transmissions to aid in living, understanding, and interpreting in relation to our time and space. Did Shah Ali really live to a hundred years? The number here operates at a different scale, to emphasise an order of magnitude, and that he was an extraordinary figure. Sparse as they are, the stories are etched out of a mythical and legendary framework with historical filigree.

But for early reformers like Waliullah and the religious revivalists, mazārs were positioned as being outside of rational and authentic knowledge, or as anti-knowledge – backward, and not of this time. In their temporal slippage, shrines were accused of dispensing superstition and fabulation, responsible for a contagion of false beliefs. Both the liberal modernists and religious purist political projects and impulses saw the presence of shrines as the presence of an adulterated system, an affront to real truth. To reach ‘pure’ or ‘rational’ truth, shrines had to be abolished, regulated, invalidated, erased – brought under control – along with the social life and knowledge they generated. If one wanted to recover a state of purity by reaching back to the past, or another to lurch forward to a future of rationalism, both of these competing strains relied on an idealisation of knowledge stripped down to facts and literal readings, confusing them for reason, discursive processes of interpretation, or multiple methods of wisdom and truth. In Waliullah’s Lal Salu, a fraud simply invents a story of a saint, and the shrine is a lie – as a matter of fact, there is nothing there, thus producing not knowledge or truth but a fantasy. For Salafi and other puritanical revivalists, knowledge is simply a selective textual and literal reading; words, terms, lines, references from the scripture carry no connotative weight, no subtext or context. Influenced by inert empiricism, these two ostensibly separate but intellectually aligned movements crafted a political and narrative worldview in which shrines were illegitimate, dishonest arbiters of faith and truth.

Any form of knowledge, whether scientific, rational, esoteric, humanist, or transcendental is discursively produced, politically mined and mimed. Science or scripture – both are housed within and woven through an interpretative field and a political process. As Seyyed Hossein Nasr reminds us:

There is nothing that is simply an external and brute fact or phenomenon because the very notion of externality implies inwardness. […] Esotericism, traditionally understood, does not negate the significance of the exoteric. […] Much of the traditional study of religions is in fact precisely devoted to sacred forms and the meanings they convey as symbols and myths without denying their historical reality and significance. (Nasr 1996, p. 16)

Without stultifying tradition or simply equating it with custom or past heritage, Nasr argues for twin processes and sources of revelation and intellection, or intellectual intuition, an illumination of the heart and mind, as avenues towards ultimate reality (Faruque 2023). Against purely literal or empiricist information, Nasr’s is knowledge as re-enchantment instead of intellectual gridlock. That shrines don’t always yield to straitjacketed empiricism isn’t politically or epistemically useful for a disciplinary social architecture used to weaponise, commodify and classify information. Instead they are co-opted as data, reducing a habitus and its subjects to governable, managed individuals against whom the information can be used. That shrines are present but cannot be present is to deny their spatial and temporal lineage and legitimacy to supplant with another. So, they are a challenge, their presence intolerable, as temporal, ontological anomalies, but being asynchronous they can also re-enchant.

Conclusion

I return again to the question of who or what lies in a shrine? Who among us is not enchanted by one fable or the another, after all, when nation states are floated on the dangerous waters of their own myths. In being cast outside, a place for cast-offs and castaway knowledge, shrines are anomalous, suspicious, troubling, and a formidable counterpose to the spatial, social considerations of a regimented society. Theirs is a present enacting oppositional time – as rejects and rejected – and in that opposition, in not being included within the rubric of a disciplinary society lies potential for stealthy resistance to unravel and trouble arrangements of brutality.