I

The notion of the exhibition as a constellation of related arguments rather than a single essay1 is one that is widely taken for granted today (Rijksakademie 2012). In what follows, I take curated exhibitions as ‘events of knowledge’ production, exchange, and dissemination, with protagonists encompassing human and non-human producers (Irit Rogoff as quoted in Lind 2021). Terry Smith has already referred to the centuries-old modality of positioning exhibitions as ‘texts’ through which curators address or speak to one another (Smith 2012, p. 204).2 Consequently, I situate the politics of curatorship squarely in relation to what the French philosopher Jacques Rancière, apropos of Jean Joseph Jacotot (1770–1840), has termed the ‘[radical] equality of intelligences’, rather than the segregation between elite and inferior powers of reasoning (Rancière 1991; Malabou 2021, p. 3; Akoi-Jackson et al. 2021, p. 13). For Rancière, stultification is what occurs whenever a subject’s will is reduced to another intelligence thought to be superior (Rancière 1991: 13). It is from this frame of reference that I shall discuss the implicit power dynamics in the pedagogical relationships between the curator, artist, artwork, public, and the expanded infrastructure within the art world.

Taking this politicisation of curatorship even further, Maria Lind has discussed the qualitative distinction between ‘business as usual’ curating – which she describes as the technical modality that enables the becoming public of art – and ‘the curatorial’ (Lind 2021; Smith 2012). The curatorial is anti-professional, in the sense that it may be practised as much by experts – artists, curators, editors, critics, historians, teachers, and so on – as by non-experts. It is aimed at creating friction and pushing new ideas (Lind 2021). In its desire to politicise exhibition making by subverting existing power relations towards new possibilities, the curatorial unsettles the status quo in its manifestation as a ‘distributed presence’, indifferent to standardised roles in exhibition practice. I read Lind’s distinction from a dialectical vantage point, such that the curatorial appears to be operational at the contingent (epi-) layer of curating, possessing a democratic force that is both emergent and disruptive, thriving on dissent and antagonism, even as it resists consensus. On this basis, one could posit that the curatorial emerges when curating is shot through by ‘schizzes, points-signs, or flows-breaks that collapse the wall of the signifier [i.e. meaning]. Because these signs have crossed a new threshold of deterritorialization’ (Deleuze & Guattari 1983, p. 242).

The collapse of the wall of signification helps in returning to the notion of contingency. Propelling us into the discourse of necessity, Nick Waterlow prescribes that the ‘belief in the necessity of art and artists’ constitutes a non-negotiable ethic of curatorship (Waterlow as quoted in Smith 2012, p. 20). This positions art as an intrinsic necessity to the exhibition situation. Curatorship, since its earliest institutionalised form until now, has also become an integral mediation for art becoming public. But it is a kind of necessity unlike art – for the simple reason that the practice of exhibition making predates curating, and that not all art exhibitions are (or ought to be) curated. Let us call its sort a contingent necessity. As Alenka Zupančič surmises: ‘[C]ontingency is not the same as relativism. If all is relative, then there is no contingency. Contingency means precisely that there is a heterogenous […] element that strongly, absolutely decides the structure, [and] the grammar of its necessity. [Therefore,] contingency is not in our power, by definition, otherwise it wouldn’t be contingency.’ (Zupančič et al. 2019, p. 446)

As far as I am concerned, curatorship, when understood as exemplifying the contingency of necessity, is what gives meaning to the practice as emergent and potentially disruptive to the exhibition form.3 Further, it appears to foreground an egalitarian hierarchy between the artist/artwork and the curator. I see nothing wrong with hierarchies, so long as they are not rooted in the logic of dispossession, and the privileges they confer are not self-justifying. According to David Graeber, there are relationships of authority that subvert their own bases.4 I am of the mind that authentic curatorial work counts as one of such relationships of authority (Graeber & Rose 2006), and that the curator with egalitarian concerns needs to come to terms with this self-abolishing dimension of difference (Rancière 1991, p. 13; Rancière 2009; Ohene-Ayeh 2024, p. 60).

II

I have elsewhere distinguished between two tendencies in curatorship. The first is what I call the curator-centred, explicative regime of ‘stultified curating’ (Ohene-Ayeh 2024). This model consecrates the curator’s self-justifying privilege to define the exhibition situation. In other words, since curators determine the why, when, who, what, where, and so on and so forth of exhibitions in the canon of contemporary art, anything that is worth learning or knowing in the context of the exhibition is to be solely derived from this curator-specialist, inadvertently leading to the dispossession of the artist, artwork, spectator, and other potential actants (Ohene-Ayeh 2024; Groys 2008). Second is the ‘incidental regime’, which I borrow from Ivan Illich’s theory of ‘incidental education’, in his seminal text Deschooling Society (1972), that desires to see ignorant persons meet about a mutual interest without the intrusions of a schoolmaster or expert (Illich 1972, p. 11, 31). Contrary to curator-centred practices, this radically inclusive model affirms the legitimacy of any person to summon a meeting (recall the ethics of the curatorial). Illich diagnoses the penchant for manipulation, immutable hierarchy, and dependency in mainstream education as follows: ‘Educators want to avoid the ignorant meeting the ignorant around a text which they may not understand and which they read only because they are interested in it.’ (Illich 1972, p. 11) Incidental practice, according to Illich, fosters a courage in the disenfranchised to ‘talk back’ and ‘thereby control and instruct the institutions’ of which they constitute an effectively excluded part5 (Illich 1972, p. 12).

A corollary of the pedagogical dynamics in the incidental order, with regards to the exhibition, is that it is neither orientated towards resolution nor understanding of the work, event, or situation at hand (keeping in mind that ignorance is an authentic pedagogical positionality). It is rather about making users of its public, since a new threshold of deterritorialisation, producing an ‘interplay of phenomena without aim or end’, has been breached (Deleuze & Guattari 1983, p. 371; Ohene-Ayeh 2022; Ohene-Ayeh 2024). To be present with, and be willing to contribute to, what is offered in the exhibition is sufficient to build connective associations, interactions, and relations, while rendering curatorial authority inoperative.6 In the same vein, this is what affirms non-human intelligences as always already present, since what we call a work of art is, without exception, an ecological situation – an ambiguous contiguity between life forms; organic, synthetic, artificial, mechanical, etc. If, for Timothy Morton, ‘ecological awareness is awareness of unintended consequences’ (Morton 2018, p. 16), then we are back to amplifying Zupančič’s proposition that some things, although necessary, are ‘not in our power’ (Zupančič et al. 2019, p. 446). This kind of ecological thinking upholds the necessity of contingency – conditioning the exhibition, or ‘meeting’, as a site that ruptures ‘our faith in the anthropocentric idea that there is one scale to rule [everything, which is] the human one’7 (Morton 2018, p. 32). And the exhibition becomes a situation where contingent knowledges are produced, since artistic and curatorial intentions immanently engender their own excesses.

III

When we sidestep the potentially stultifying question ‘What does this mean?’ (which requires an explicator) in our encounter with art, and slip into the affirmative ‘What does this do? (Deleuze & Guattari 1983, p. 166–183; Ohene-Ayeh 2022), ignorance is no longer a disease to be cured with explanation but a generic condition of ‘not-knowing’8 that satisfies the minimal conditions out of which contingent, slippery, and even strange knowledges may emerge (Rancière 2009, p. 9; Ohene-Ayeh & Fakeye 2023; Ohene-Ayeh 2024(a); Ohene-Ayeh 2024).

When the artist-philosopher kąrî’kạchä seid’ōu, of whom I will speak later, posits that ‘art is something that is radically new’, we gain another perspective into what I have been talking about. ‘Being a subject of the radically new,’ he contends, ‘can be quite unsettling [since] one has to learn to come to terms with the premises of the new terrain.’ (Bodjawah et al. 2021, p. 24) The radically new, essentially ex-centred, has no privileged position from which it emerges. It engages the paradox that while art is the outcome of some sort of intention, it is also plagued by ‘unintended consequences’ as it manifests in symbolic, virtual, material, and/or traumatic forms alike. It is often the case that at the time of the exhibition, even though the work has already been made (or is in the process of production), its maker(s) may lack the language or ability to articulate, comprehend, or even contextualise the work, and would need to develop new tools or vocabularies to come to terms with the outcome(s) of their own labour. And being ecologically aware does nothing to undermine the intelligence in question. Therefore, the subversive pedagogical context in the aesthetic experience of art affords instances where meaningfully embarking on a journey of mutual discovery on the basis of ignorance (or ‘helplessness’, as the surrealist artist Louise Bourgeois might put it) is also plausible.

Bourgeois doubles down on this point when she opines, in one of her interviews with Art21, that ‘a work of art doesn’t have to be explained’ (artnet 2022). She continues by saying: ‘If you say ‘What does this mean?’, if you do not have any feeling about [the artwork], I cannot explain it to you’ (Art21 2001; artnet 2022). I agree with her in the sense that 1) Cognition is itself plagued by gaps, uncertainties, ignorances, and other such disruptions. This is the lesson of psychoanalysis in its formulation of and insights into the existence and workings of the unconscious, as the ‘essential articulation of non-knowledge’ in every thinking subject (Lacan 1997, p. 295). The reference here is to knowledge that is unaware of itself, and yet is universally present in each and every one of us (master, slave, artist, spectator, critic, etc.). 2) Art, in its radicalness, does not always manifest in symbolisable forms. No artist (and of course, no curator), truly speaking, knows everything about what they have made. If the outcome of their labour is to remain consistent with the tenets of experimentation, then it is also legitimate to learn from what one is doing or has made. This only goes to show that whatever our definition of art is, the experience of it cannot be reduced to our cognitive faculties alone, and the incidental regime inheres such unruly provocations.

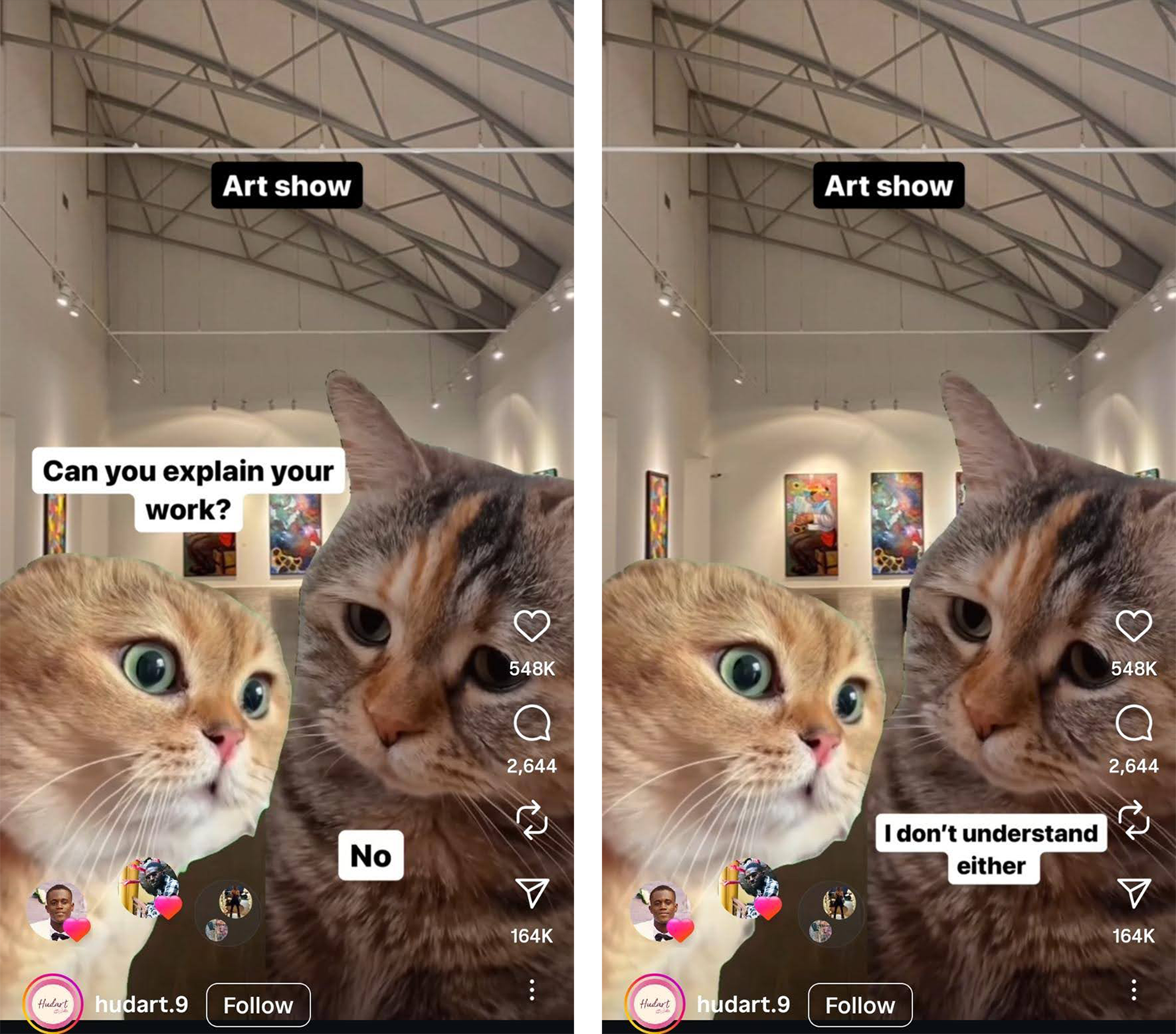

To risk overburdening this point, let me, furthermore, take the example of the viral meme depicting two cats at an art show (hudart.9 2023). The narrative goes something like this: One cat shows up to the exhibition. Bewildered by the pictorial works on display, they ask the cat next to them, ‘Are you the artist? To which the other cat replies, ‘Yes.’ The curious cat beseeches their interlocutor with the follow-up question, ‘Can you explain your work?’ The sombre answer they receive is, ‘No. I don’t understand it either.’ (Figure 1) This short dialogue (whether cynical, dismissive, or otherwise of non-narrative artworks) manages to take us back to the intersubjective scenario that Illich described. If we take the artist-cat to be Bourgeois, who sidesteps explicatory prowess in favour of a will-to-will relationship (Rancière 1991), exhibitions become fertile grounds for the production of ‘illiterate knowledges’ (Ohene-Ayeh 2024. p. 13; Rancière, 1991). The lesson here is that ignorance is not the opposite of knowledge but a kind of knowledge in itself, even if of a lesser kind (Rancière 2009, p. 9). Thus, pedagogical exchanges, rather than always being determined by a self-justifying authority, can also be driven by mutual ignorance. The collective will to be present and to work something out, without any burden of sophistication, is what is emphasised – since, for whatever it’s worth, the questioner is actually present at the exhibition out of interest.

IV

To critique the centrist (stultifying) model, which positions the curator as a sovereign exhibition maker (Smith 2012, p. 113), and the shortcomings of curatorial explication, the Cuban curator Gerardo Mosquera has made the counterintuitive suggestion that ‘nowadays we curators have to work from a certain awareness of our ignorance’9 (Rijksakademie 2012). Rather than the insidious explicator who has the special privilege to set both epistemic and ontological parameters for art, Mosquera’s suggestion lends credence to ecological awareness while offering a political attitude to the historical problematic of imperialist exhibition practices stemming from the nineteenth century. Mosquera would know more than a thing or two about taking such a subversive position, since he co-curated the inaugural Bienal de la Habana trilogy (1984–89) that has retroactively served as a watershed moment in remodelling the hegemonic transnational exhibition format on democratic terms (Weiss et. al 2011; Rijksakademie 2012).

One of the key political projects of the Bienal, according to Rachel Weiss, was to ‘formulate a Third Worldist cultural proposition not based in the fictions of cohesion’ (Rijksakademie 2012). Shifting from the competition-driven ‘radio model’ of exhibition making predominant in the Western world, the early editions of the Bienal offered an eccentric alternative to the trade fair-inspired Venetian paradigm (Filipovic et al. 2010, p. 306–321; Belting 2013; Marchart 2023). According to Mosquera, the second edition of the Bienal is ‘the first global contemporary art show ever made’. Not only because it happened three years before Jean-Hubert Martin’s infamous Magiciens de la Terre (1989), but also in terms of its scale, as it presented more than fifty exhibitions and events, showing 2 400 works made by 690 artists from 57 countries (Rijksakademie 2012; Weiss et al. 2011). Among the innovations pioneered by the Bienal in the post-war era, are replacing the national representation/pavilion system with a thematically driven exhibition; programmatically dispersing the exhibition into smaller clusters of happenings distributed throughout the city of Havana, thereby breaking the centrality of the main exhibition; treating the exhibition as a ‘porous organism’ rather than as a stable system; and collectivising curatorial work (Rijksakademie 2012; Weiss et al. 2011). Since then, such strategies have become a mainstay in transnational exhibition planning.

This ‘queering’ of the biennial format (to borrow Mosquera’s words again), akin to seid’ōu’s ‘radically new’, subverts the homogeneity of meaning/understanding for all who are implicated. At the very least, it also allows us to earnestly practise the ‘awareness of our ignorance’ (or ‘helplessness’) to be able to stage scenarios where an ignorant person can meet another ignoramus based on interest, without being stalked by a master explicator (curator, artist, teacher, critic, etc.), resulting in the inadvertent subordination of one intelligence to another (Illich 1972, p. 11; Rancière 1991). This potentiality is rendered all the more relevant when the exhibition is treated as a discursive environment, characterised as much by display as it is as a site of discussion and knowledge production.10 Being among the earliest large-scale exhibitions to make the discursive turn in the transnational mainstream, the eccentricity of the Bienal buttresses Mosquera’s insight that no curator could possibly totalise the speculative, generic, and contingent dimensions evoked by the incidental exhibition-as-organism. It is therefore much more strategic to embody this lack, or finitude, and use it as the basis to explore new horizons than to be deluded by the myth of absolute mastery. If this is so, then the curator is not always an enabler, nor teacher, nor expert in the context of any given exhibition project. By Graeber’s logic, such forms of authority must self-subvert (or practise self-criticality) in order to restore egalitarian relations, and so the curator also becomes a learner, participant, flâneur, spectator, and so forth, in what they themselves have initiated as the exhibition situation.11

V

My exposition on reading the exhibition as a pedagogical situation, which inheres the prospects of radicalising the exhibition form, is concretised in the examples of Bisi Silva (1962–2024) and kąrî’kạchä seid’ōu (b. 1968)12 in their active deployment of pedagogical-curatorial models with emancipatory aims, while depositing seeds of revolution in art education and professional practice in Nigeria and Ghana respectively.

Silva was an independent curator and director of the Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA) Lagos – an institution she founded in 2007 to foster experimental approaches to art, and to augment the dearth of contemporary art structures in Lagos at the time. She describes CCA Lagos as a curatorial laboratory – a discursive platform characterised by critical debates and exchanges which facilitates talks, panel discussions, seminars, workshops, exhibitions, and publications bearing local and global resonances (Silva 2017, p. xv).

Silva also founded Àsìkò Art School – the programme that coalesces residency, workshop, professional development, and art-school models – in 2010 in Lagos. She was motivated to dwell on the pedagogical dimension of curatorship not only for its potential for knowledge sharing, but also as a ‘self-critical form of curatorial inquiry’ (Silva 2017, .p xv). Maintaining this self-critical posture is crucial to any progressive approach to art practice and curatorial work today. In effect, what Mosquera is advocating is that, in addition to working with what we know, we should also be sensitive to the fact that there is more to be sought in the deterritorialised ‘breaks-flows’ of knowledge. This is probably why Silva specified the ethos of Àsìkò13 as a space that encourages ‘learning to unlearn’ (Silva 2017, p. xvi). It is an equally instructive proposition by which to comprehend why Oyindamola Fakeye, the present Artistic Director of CCA Lagos, would assert that ‘not knowing is our pedagogy, and we’re thinking about how we can continue to not know in order to learn,” with respect to Àsìkò (Ohene-Ayeh & Fakeye 2023). In this way, she is devoutly carrying on Silva’s legacy in sustaining institutions and models that affirm what we have variously called ecological awareness, incidental education, and illiterate knowledges. (Morton 2018; Illich 1972; Ohene-Ayeh 2024(a); Ohene-Ayeh 2024; Rijksakademie 2012). In so doing, she is devoutly carrying on Silva’s legacy in sustaining institutions and models that affirm what we have variously called ecological awareness, incidental education, and illiterate knowledges (Morton 2018; Illich 1972; Ohene-Ayeh 2024(a); Ohene-Ayeh 2024; Rijksakademie 2012).

Moving on, kąrî’kạchä seid’ōu (formerly Edward [Kevin] Amankwah) is the street-artist-turned-professor, polymath, and ‘subversive intellectual’ (Harney & Moten 2013, p. 26) whose dematerialised art practice has, over the past two decades, inspired an aesthetic revolution in Ghana. seid’ōu identifies as a ‘teacher whose workings are not typically counted as that of a teacher within the university’, and as ‘an artist within the artist community whose workings are not typically counted as that of an artist’ (seid’ōu & Bouwhuis 2014, p. 111). It is within this paradox – defined as much by precarity and fugitivity as it is by impossibility – that I consider him to embody the self-subversive principles under discussion so far, with the emancipatory verve of self-embodying an alternative to the status quo (Graeber & Rose 2006). He is the ‘vanishing mediator’ (Bodjawah et al. 2021; seid’ōu 2006) to which the blaxTARLINES KUMASI ‘silent revolution’ can be traced. blaxTARLINES is an open-source art collective inspired by seid’ōu’s non-proprietary practice. Since its inception in 2015, blaxTARLINES’ guiding axiom, articulated by seid’ōu about his own practice, has been to transform art from the status of commodity to gift (Bodjawah et al. 2021; seid’ōu & Bouwhis 2019, p. 193). Thus, blaxTARLINES operates as a sharing community, a transgenerational, and transcultural network inspired by key moments in emancipatory politics.

In 2003, seid’ōu joined the Department of Painting & Sculpture under the Faculty of Art at the College of Art,14 Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi, Ghana. This was when he embarked on what he calls an ‘artistic strike’ to ‘stop making art symbolically and to inaugurate a practice of “making artists”’15 in his alma mater (Akoi-Jackson et al. 2021, p. 14; seid’ōu & Bouwhuis 2019; Ohene-Ayeh 2018). This desire was shaped by what he deemed to be the failure of effecting long-term changes during his MFA days (1993–1995) when he and his colleagues’ deskilled, dematerialised, playful, and conceptual experiments at the Department were curtailed by the beaux-arts-inclined faculty at the time (Akoi-Jackson et al., 2021, p. 15).16 seid’ōu considered his Emancipatory Art Teaching Project17 – the ongoing pedagogical project he implemented when he became a member of the faculty – as a gesture of ‘retroactive redemption’18 to reignite the emancipatory vitality of the experiments that his MFA cohort had been practising in the early to mid-1990s (Akoi-Jackson et al. 2021; seid’ou 2006; Ohene-Ayeh 2018).

seid’ōu’s pedagogical project set the conditions to go through the curriculum of the KNUST Painting programme, rupture it, and set loose its immanent potentials in a way that enabled students to set their own bounds and take responsibility (Akoi-Jackson et al. 2021, p. 15) instead of the stultifying ‘client-server’ order where students are merely tutored as ‘assignment-making learners’ under the instruction of ‘assignment-purveying teachers’ (seid’ōu 2006, p. 289). The palpable influence of this ‘talking back’ model is self-evident in art education, particularly at the KNUST Department of Painting & Sculpture in Kumasi, and is inspiring extant approaches to intellectual emancipation in Ghana presently. Such a crisis is reminiscent of G.K. Chesterton’s radically immanent dialectics, likened to the reality of being in a fire, a battle, or a shipwreck, to the extent that ‘there is no way out of the danger except the dangerous way’ (Chesterton 1927, p. 131). seid’ōu prefers Matias Faldbakken’s phrasing that ‘to escape horror, bury yourself in it’ (Faldbakken as quoted in seid’ōu & Bouwhuis 2014, p. 111) and the emancipatory politics of the demos, who are the excluded subjects from politics but who insert themselves into the bigger picture, on their own terms, on the basis of the universal announcement, ‘but we are all equal?’ (Akoi-Jackson et al. 2021, p. 13; Rancière 2004).

In conclusion...

It is the incidence of contingency that legitimises the right, power, and privilege of the curator to ‘summon others’ or ‘call a meeting’ (Illich 1972, p. 31, 40; Ohene-Ayeh 2024) in the context of being responsible for a public exhibition, where the simultaneous processes of self-direction as well as learning with and from others (persons and things) can happen among equals. This is what de-operationalises the curatorial role and dignifies it as essential to the exhibition situation. If the curator-subject in the stultifying regime encroaches the space of intellectual equality by enforcing the hegemony of understanding solely on their terms, the obverse subject in the incidental or emancipatory regime produces conditions and experiences that facilitate illiterate knowledges.