Opening the wound, an introduction

Grotesque aesthetics refuse containment. They resist order, coherence, and beauty as defined by the dominant gaze. In their excess, in their distortion, they open something else, something unruly, wounded, and strange. They do not offer comfort; they demand confrontation.

In the wake of colonialism and its enduring afterlives, the grotesque becomes more than a visual technique. It becomes an aesthetic language for what history tried to erase but never quite managed to kill. Across contemporary African cinema, the grotesque operates not as horror for horror’s sake but as a radical reimagining of form and feeling. Through fractured bodies, temporal dislocation, and spectral hauntings, these films make space for what remains ungrievable, unspeakable, and unfinished.

Sylvia Wynter reminds us that colonialism was not merely a political or economic system but a project of ontological control, defining who counts as human and who does not. The formulation of ‘Man’ as over-represented and self-universalising offers a powerful diagnostic of how colonial epistemologies sought to degrade, distort and erase non-Western modes of being (Wynter 2003). Yet, to begin with this violence as the primary referent is to risk inadvertently reinscribing the power it sought to impose, centring the European gaze once more.

Instead, what if the grotesque, as it emerges in The Bloodettes (Bekolo 2005), Specialised Technique (Igwe 2018), and This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (Mosese 2019), is not primarily a reaction to Western visions but an emanation from local cosmologies, ancestral knowledge systems, and ritual traditions refracted through cinematic form? In The Bloodettes, the grotesque becomes a futuristic satire where post-independence decay collides with occult politics. In Burial, it is the presence of spirits and the porousness between life and death that resist the state’s developmentalist logic. In Specialised Technique, archival fragments speak through sonic disturbance.

Here, the grotesque is not an aesthetic of abjection but a cosmological modality. Its excess and distortion are not symptoms of damage but of the density of meaning that exceeds colonial legibility. Within African and Indigenous worldviews, fragmentation, spectrality and excess are not always pathological. They can be sacred, strategic, and resistant. The grotesque, when rearticulated through epistemologies, is not reactive to Western canons, it is a method of articulating the unseen and disavowed. It distorts the colonial gaze and undoes the authority to see it all.

These are not broken worlds waiting for repair. They are fragments that pulse cosmological intelligence. What looks like ruin is also a site of recursion and radical possibility. (Further articulation of the wound and the speculative openings it enables will follow.)

To understand the grotesque as a decolonial aesthetic, it is important to begin with its origins and cultural significance. Frances S. Connelly traces the term to grottesca, meaning ‘of the grotto’, a reference to the subterranean spaces of ancient Roman ruins rediscovered during the Renaissance. The grotto is a cave, a recess, an open cavity, and a symbolic site of duality: fertility and death, mystery and emergence, the sacred and the subterranean. In Connelly’s words, ‘It is a space where the monsters and marvels of our imagination are conceived’ (Connelly 2012, p. 1). The grotesque, then, is not merely about horror or distortion; it is a liminal zone where boundaries dissolve and contradictions flourish. It is the birthplace of the impossible.

In Western art, the grotesque has historically functioned as a mode of aesthetic disruption – a visual logic of contradiction that slides between beauty and decay, the comic and the monstrous, the familiar and the alien. Connelly argues that its critical power lies in this ambivalence it provokes and unsettles, not by rejecting form but by unravelling the cultural coherence that form pretends to offer. The grotesque is partly abject, partly sublime; it reveals what lies beyond the limits of rationality, exposing the chaos beneath order, the body beneath ideology, the horror beneath beauty. It opens a space not only for fear or disgust but for awe at the unresolved complexity of being.

Importantly, Connelly situates the grotesque as an historical mirror, reflecting the specific anxieties and contradictions of its moment. In the Renaissance, it evoked tensions around nature, monstrosity, and divinity. In the Enlightenment, grotesque figures threatened emerging systems of reason and classification. In the twentieth century, grotesque imagery became a response to absurdity, trauma, and alienation. Across these contexts, the grotesque does not merely distort the body, it distorts meaning. It exposes how deeply aesthetics are tied to political, social, and epistemological orders.

Unlike beauty, which soothes, or the sublime, which elevates, the grotesque lingers in ambiguity. Its figures are hybrid, in flux, caught in mid-transformation. They resist categorisation and threaten the logic of classification. For Connelly, the refusal to resolve – to be one thing or another – makes the grotesque a site of epistemic anxiety, a space where the limits of knowledge and perception begin to fray.

Yet while Connelly locates the grotesque within European art-historical tradition, the concept is reorientated here through a southern epistemological lens – rooted in decolonial thought, Caribbean theory, and African visual cultures – one in which grotesque aesthetics emerge as countercolonial strategies rather than reflections of Western cultural anxiety. It is important to note that Connelly’s analysis, while illuminating within a Western frame, does not engage with decolonial thought or southern epistemologies. Her work remains rooted in a Eurocentric art-historical tradition. As such, this project draws on her formal and historical insights, but departs from her framing by resituating the grotesque within anti-colonial and postcolonial worldviews.

Sylvia Wynter’s theory of the ‘Genre of Man’ sharpens this tension. In Unsettling the Coloniality of Being, Wynter argues that colonialism was not only a political and economic system, but an ontological one, which redefined the human itself. Colonial modernity, she writes, produced a narrow, hierarchical definition of the human: white, Western, Christian, rational. This figure, what she calls Man, served as the idealised benchmark for personhood, against which all other forms of life were deemed irrational, monstrous, or grotesque (Wynter 2003). As such, the grotesque is not merely an artistic category but a colonial designation, a means of rendering certain bodies and beings as excessive, unruly, or subhuman.

Wynter outlines two phases of this figure: Man1, rooted in the Christian theological view of the rational soul made in God’s image, and Man2, the secular, Enlightenment-era figure defined by reason, science, and economic utility. This latter form that is bourgeois, European, male, heterosexual became the dominant genre of the human. Those outside of it – the colonised, enslaved, racialised, poor, and gender-nonconforming – were cast outside the category of the human altogether.

Scholars such as Achille Mbembe and Ariella Aïsha Azoulay help further illuminate how visual regimes shaped by coloniality continue to define visibility, legitimacy, and the human. Mbembe’s ‘aesthetics of the vulgar’ (Mbembe 2001) in On the Postcolony aligns with the grotesque as expressions of the unruly, the excessive, and the violent under postcolonial conditions. Similarly, Azoulay’s call for ‘unlearning imperialism’ (Azoulay 2019) invites a reorientation of visual epistemologies away from the imperial archive and towards the lived, fractured realities of those it disfigured.

From the South, theorists like Walter Mignolo emphasise the importance of epistemic disobedience. Their work urges a reading of form not merely as aesthetic but as deeply political – embedded in colonial histories of suppression and refusal. When grotesque aesthetics emerge in African cinema, they carry this weight, not as reflections of Western absurdity but as insurgent strategies that make visible what was meant to be erased.

Grotesque aesthetics in African cinema directly challenge this fabricated hierarchy. They foreground bodies and forms that violate the visual and ideological coherence of Man2. These aesthetics refuse the rationality and order that sustain the colonial definition of the human, and instead centre the spectral, the wounded, the erotic, and the disfigured figures that are illegible to dominant frameworks but fully alive in their own right. For Wynter, the solution is not to assimilate into the Genre of Man but to invent new genres of being human – ones grounded in storytelling, ecology, embodiment, and collective life. Grotesque aesthetics, with their emphasis on excess, refusal, and transformation, open space for such reimagining.

In this sense, grotesque aesthetics align with a broader southern tradition of visual and narrative resistance. They are not anomalies or aberrations but part of a continuum of insurgent artistic expression that reclaims the right to opacity, incoherence, and affective excess as sites of knowledge and being. As Édouard Glissant writes in Poetics of Relation, the right to opacity is not about concealment but about resisting the colonial demand for transparency and total comprehension (Glissant 1997). In this way, grotesque forms embody a refusal of colonial legibility; they reject being fully known, classified, or assimilated. Instead, they insist on existing otherwise: relationally, fugitively, and in excess.

Grotesque aesthetics are often dismissed as excessive, irrational, or abject, figures of distortion relegated to the margins of taste, beauty, and order. Yet it is precisely this marginality that gives the grotesque its critical power. In contexts marked by colonial violence and its ongoing afterlives, the grotesque offers a mode of disruption. It refuses the terms of legibility set by colonial modernity and challenges the very foundations of what counts as human, beautiful, or true.

As mentioned earlier, Sylvia Wynter’s theory of the ‘Genre of Man’ provides a crucial framework for understanding this refusal. She argues that colonialism was not only a material project of conquest but an ontological one. It redefined the human through a racialised, Eurocentric model of rationality and order. This figure (Man1) became the measure of all life, producing a violent hierarchy in which Black, Indigenous, and colonised peoples were cast as grotesque: irrational, excessive, monstrous.

To be made grotesque by the colonial gaze is to be positioned outside the bounds of the human. But in the hands of contemporary filmmakers, this positioning is redirected. What appears as a pathology under colonial regimes is reworked as praxis. In this shift, the grotesque ceases to function as a colonial category of degradation and instead becomes a site of strategic unrecognisability to dissolve colonial authority altogether.

Rather than seeking inclusion within the category of Man, decolonial aesthetics engage in what Mignolo calls epistemic disobedience, a refusal to accept colonial ways of seeing and knowing as universal. The grotesque does not correct or soften the image of the Other. It distorts, ruptures, and destabilises dominant modes of representation. In this way, grotesque aesthetics operate as a form of unlearning, undoing the visual and ideological order that upholds the colonial matrix of power.

Saidiya Hartman’s theorisation of the afterlife of slavery further illuminates this move. The present, in her work, is haunted by unresolved forms of racial subjection. The grotesque becomes the visual and affective register of that haunting, where coherence collapses and the body, memory, and archive return in fractured, unsettling forms (Hartman 1997). In this context, grotesquerie is not a spectacle of suffering but a counter-aesthetic that renders visible what the liberal humanist frame cannot contain.

Contemporary filmmakers do not mimic colonial distortion, nor do they sanitise it. Instead, they redirect its logics, fracturing time, refusing coherence, invoking spirits to create a visual language that draws from cosmological and ancestral intelligences. The grotesque is no longer a mark of dehumanisation; it becomes a modality of knowing and being otherwise.

To embrace the grotesque, then, is to move through discomfort towards confrontation. It invites us to sit with rupture, to encounter forms of being that exceed Western expectations of coherence or beauty. As a decolonial praxis, the grotesque disfigures the colonial gaze and opens space for aesthetic and ontological reinvention.

The Bloodettes: Erotic grotesque and gendered resistance

Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s The Bloodettes (2005) enacts the grotesque as a deliberately excessive, insurgent aesthetic, one that confronts the Cameroonian neocolonial present through an Afrofuturist, feminist lens. Set in a speculative Cameroon of 2025, the film follows two high-class sex workers, Majolie and Chouchou, as they move through elite spaces saturated with corruption, occult dealings, and necropolitical violence. But rather than positioning these women as victims, the film frames their erotic flamboyance, ritual gestures, and transgressive femininity as acts of resistance. The grotesque is not a collapse of form here; it is the only form capable of speaking to the entanglement of power, performance, and myth in postcolonial Africa.

The narrative is fractured, surreal, and filled with temporal distortions, a strategy that echoes the epistemic disruption at the heart of the film. Majolie and Chouchou navigate a chronopolitical terrain of loops, glitches, and metaphysical visitations. Voice-over narration breaks the fourth wall, camera angles shift erratically, and moments of sci-fi futurism blend with ancestral cosmologies. These techniques rupture cinematic coherence, mirroring the film’s deeper philosophical aim: to dislodge colonial-modernist linearity and gesture towards a cyclical, haunted temporality rooted in African spiritual traditions.

In an early scene, Majolie performs a harnessed aerial dance, her body suspended like a marionette. The camera circles her as she twists mid-air, adorned and eroticised, yet entirely in control. This scene parodies colonial surveillance and objectification – her body is made a spectacle and a weapon. She is not merely watched; she orchestrates the gaze. It’s an uncanny performance of femininity that queers bodily autonomy, underscoring how the grotesque renders the erotic both alluring and threatening.

Later, in one of the film’s most intimate moments, Majolie is shown bathing naked, her body tenderly lit and slowly immersed in water. The camera lingers on her flesh to centre acts of care, ritual, and self-ownership. Her movements are slow, deliberate. The scene recalls the imagery of spiritual purification, a moment of solitude and reclamation in a world that otherwise seeks to commodify and degrade her body. The erotic and grotesque intersect here: nudity is sacred, strange, and sovereign.

Central to The Bloodettes is its invocation of the Mevungu, a real-life secret matriarchal society in Central Africa associated with female initiation, fertility, and ancestral power. Bekolo situates Mevungu as a counter-hegemonic force, one that predates and outmanoeuvres the patriarchal violence of the postcolonial state. The women’s alignment with Mevungu gives spiritual depth to their aesthetic and political gestures. Their erotic transgressions are rituals, cosmological interventions. When the Mevungu is invoked – through drumbeats, rhythmic chants, and dreamlike sequences – the film collapses linear temporality and asserts an enduring feminine sacred order.

The grotesque, in this world, is an epistemic revolt. Drawing on Wynter’s theory of the ‘overrepresented Man2’ (Wynter 2003), Bekolo’s heroines are excessive, irrational, emotive – everything that the colonial order sought to eliminate or contain. Majolie and Chouchou revel in this excess. They navigate male-dominated institutions by subverting them through seduction, performance, and embodied refusal. Their grotesqueness is strategy.

In this sense, The Bloodettes performs the ‘epistemic disobedience’ that decolonial theorists like Mignolo and Wynter discuss (Mignolo 2011; Wynter 2003). Rather than reproducing the rupture of the colonial-modernist break, the film stitches together precolonial and postmodern motifs to assert a continuum. The speculative future it envisions is not one of progress or salvation, but one haunted by suppressed cosmologies – spirits, rituals, myths – returning to demand presence. The grotesque is thus a portal: it reanimates those cosmologies through interruption, parody, and spectacle.

This becomes especially clear in how the film engages with Saidiya Hartman’s theory of the painted Black body as spectacle. In Scenes of Subjection, Hartman outlines how enslaved Black women were forced to perform joy and submission under violent surveillance (Hartman 1997). The Bloodettes restages that dynamic, but flips it. The eroticised Black female body is still on display, but the effect is distorted: too stylised, too performative, too self-aware to be consumed uncritically. The women are both within and beyond the frame of colonial visuality. Their beauty, their grotesqueness, their nudity – it all resists interpretation.

Bekolo offers no redemption arc, no narrative closure. Instead, The Bloodettes lingers in blood, seduction, contamination. This is not a utopia but a saturated present where survival demands theatricality, cunning, and hauntological awareness. If there is power here, it comes through distortion. Through the refusal to be fixed. Through the grotesque.

Ultimately, The Bloodettes shows that liberation for Black women in the postcolonial world may not come through purity, rationality, or coherence. It may come through the body being undisciplined, erotic, and ritualised. Through interruption. Through myth. Through the grotesque.

In Scenes of Subjection, Saidiya Hartman offers a piercing account of how Black bodies under slavery were conscripted into scenes of spectacle that were forced to perform joy, submission, and docility in front of their oppressors. These coerced performances were not simply acts of violence but complex displays where pain and resistance existed in uncomfortable proximity. Hartman calls this the ‘staged pained body’, a body that is both punished and made visible, both silenced and spectacularised (Hartman 1997).

Her work challenges the very notion of representation when it comes to Black suffering. What does it mean to look at pain? What forms of violence are reactivated in the act of witnessing? For Hartman, the archive of slavery is filled with moments where the humanity of the enslaved is both hypervisible and completely effaced with moments of performance that were misread as contentment, loyalty, or harmony. These misreadings were not mistakes; they were foundational to the racial order.

This tension between enforced visibility and real pain, between performance and power, is where the grotesque reemerges as a political language. In Hartman’s framing, the grotesque is not simply an aesthetic of the distorted or the uncanny, but a structure of ambivalence that defines the racialised body. It holds contradiction: a body made to dance in chains, a song sung through grief, a spectacle that conceals subjugation.

Crucially, Hartman does not advocate for a more accurate or transparent representation of pain. Instead, she calls for a method of redress, a rejection to replicate the violence of the archive by simply displaying the body again. This refusal aligns with grotesque aesthetics, which disfigure the expected, disturb form, and resist clarity. The grotesque does not offer comfort or closure; it unsettles. It invites a reckoning.

Through Hartman’s lens, grotesque performance becomes a critical site of historical echo, a space where trauma resurfaces not as narrative but as fracture and distortion. The pained body is not healed, resolved, or redeemed. It is re-presented in all its haunted complexity, demanding a different kind of witnessing – one that does not seek mastery or comprehension but stays with the discomfort.

In this way, Scenes of Subjection deepens the stakes of grotesque aesthetics. It reveals how performance itself has always been entangled with Black life under racial capitalism. And it asks us, urgently, to think about what forms of seeing and storytelling can truly redress that legacy.

Redressing the archive: Saidiya Hartman and the grotesque refusal in Specialised Technique

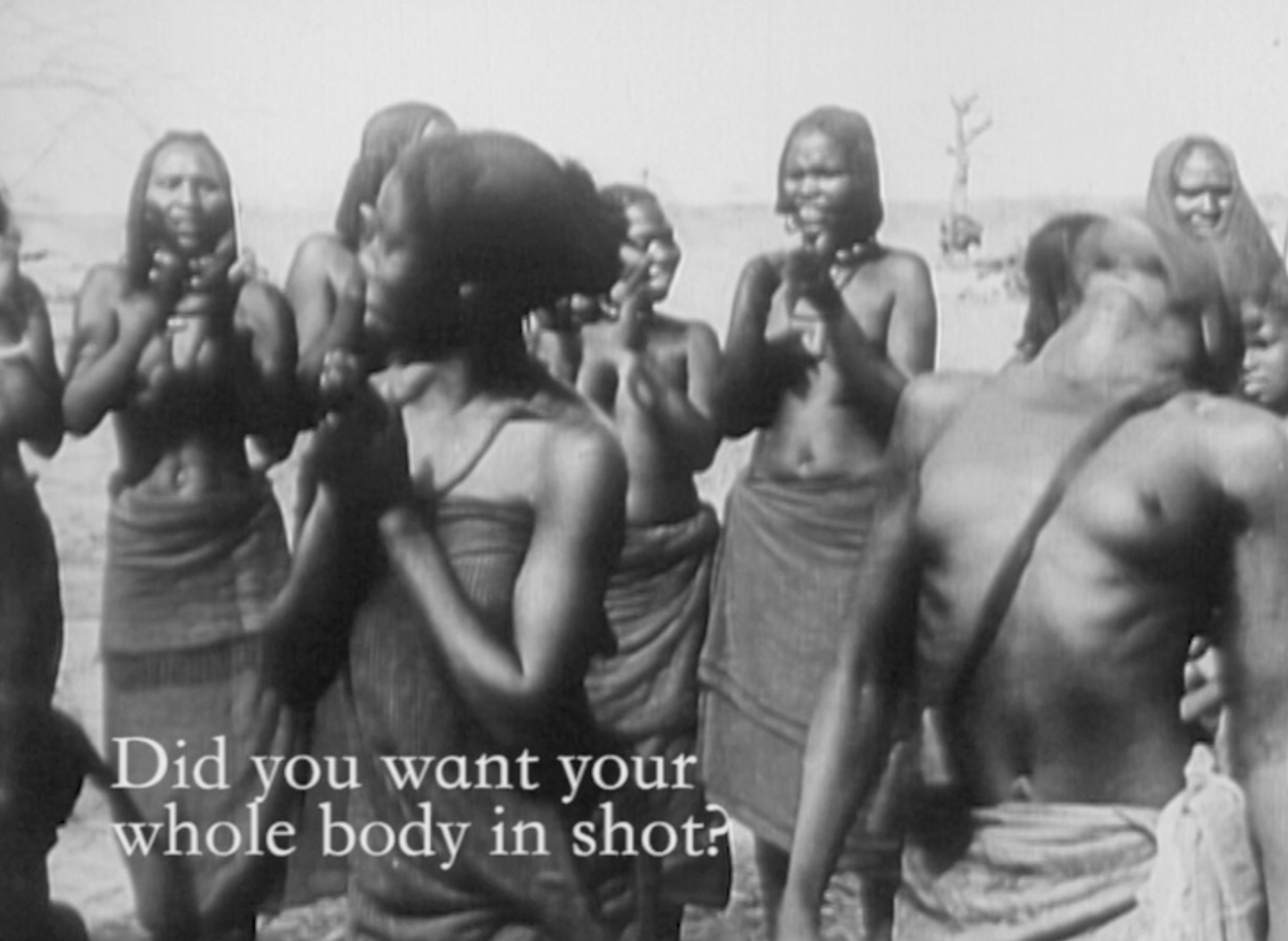

In Scenes of Subjection, Hartman interrogates the visual and performative economies that shaped the experience of enslaved people, particularly through coerced expressions of joy and spectacle. In her essay ‘Redressing the Pained Body’, Hartman warns against the representational dangers of re-enacting trauma. She asks: How do we represent Black suffering without reproducing the violence of that gaze? (Hartman 1997) This question is confronted in Onyeka Igwe’s Specialised Technique (2018), a short film that dissects the very terms of archival legibility by confronting the visual logics of the Colonial Film Unit (CFU) – a British colonial propaganda division founded in 1939 that used film as a pedagogical and disciplinary tool across Africa and the Caribbean. The CFU’s aim was to train, discipline and ‘improve’ colonial subjects. Its productions, including hygiene films, agricultural training videos and development shorts, were less about communication and more about encoding a visual order where Black bodies were rendered docile, sanitary, labouring and knowable.

And rather than restore or critique these archival images through exposition or commentary, Specialised Technique disfigures the project. Igwe’s film never gives us the comfort of a coherent narrative. There is no linear restoration of history, no redemptive account of resistance. Instead, the film fractures sound, loops voice-over, and fragments moving images. The result is disorientation – intentional, affective, and deeply political. This is the grotesque at work – not in monstrous bodies but in the disruption of form itself. What might appear as aesthetic experimentation is, in fact, an ethical methodology. It is a refusal to restore the colonial gaze to coherence.

Where Hartman critiques the impulse to make pain visible in familiar or consumable ways, Specialised Technique insists on opacity. Its formal language enacts what Hartman calls a redress, not by offering representation, but by withholding it. It disallows the viewer from settling into a posture of voyeuristic empathy. Instead, it implicates the viewer in the very difficulty of witnessing. The grotesqueness here is not excess for the sake of provocation but a tactic of resistance, one that destabilises the presumed transparency of image and sound.

The grotesque archive, as Igwe constructs it, is filled with ghostly fragments, suggestions of labour, surveillance, and racial violence that never resolve into a full picture. This is where Hartman’s theory resonates most sharply. Rather than restage the pained body, Igwe distorts the visual field until all that remains is echo, texture, and the sound of absence. The film offers no spectacle of suffering. Instead, it gives us the disfigurement of history as a more honest form of mourning.

Through this formal grotesqueness, Specialised Technique embodies Hartman’s challenge: to tell an impossible story and still leave room for the body. It is a cinematic act of epistemic disobedience, refusing to let the colonial archive retain its authority, refusing to make the invisible simply visible. What we get instead is a counter-visuality that is speculative, haunted, and unresolved.

In that way, Specialised Technique becomes a model for how grotesque aesthetics can operate in a decolonial framework – not to correct the record but to fracture it beyond recognition. To redress the pained body is not to represent it clearly, but to allow it to speak through interruption, through dissonance, through what is withheld. And that is what makes this grotesque: not what is shown, but what remains fugitive.

Walter Mignolo’s concept of epistemic disobedience, first articulated in The Idea of Latin America (2005) and expanded in The Darker Side of Western Modernity (2011), offers a crucial framework for understanding the radical potential of grotesque aesthetics in African cinema. For Mignolo, colonialism was not just a project of material conquest but one of epistemological domination. Western modernity installed its own systems of knowledge, perception, and reason as universal, rendering other ways of knowing – Indigenous, African, diasporic – to be embodied as irrational, illegible, or grotesque. Epistemic disobedience is the act of rejecting these colonial frameworks – not to offer alternative knowledge within the dominant system, but to refuse its terms altogether.

Grotesque aesthetics enact this disobedience not only by disrupting form but by disturbing how we come to know, see, and make sense of the world. In African cinema, grotesque images marked by fragmentation, distortion, opacity, and excess disrupt the aesthetic coherence and linearity that define Western cinematic language. They destabilise the visual grammar that privileges clarity, mastery, and reason, offering instead affect and ambiguity. The grotesque becomes a visual method of decolonial unknowing.

This framework finds vivid expression in Igwe’s Specialised Technique, which refuses the archival image as a site of truth. Through visual dissonance, stuttering frames, and disjointed voice-overs, the film enacts Mignolo’s ‘epistemic refusal’. It does not correct the colonial record; it undoes it, foregrounding absences, gaps, and what cannot be retrieved. In this way, the grotesque form becomes a technique for mourning without fetishisation and remembering without reinscription.

Naked Reality: Epistemic haunting and grotesque futurity

Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s Naked Reality (2016) imagines a grotesque futurity shaped not by bodily mutilation but by disembodiment, psychic dislocation, and the erasure of cultural memory. Set in a dystopian Africa a hundred years from now, the film follows Wanita, a spectral protagonist navigating a hyper-technologised landscape where ancestral ties have been severed and individual identity dissolves into digital abstraction. The grotesque in this context is affective and ontological, manifesting as temporal collapse, loss of coherence, and metaphysical exile.

Bekolo’s visual and sonic language mirrors this estrangement. Wanita moves through sterile, clinical spaces that resemble both operating rooms and metaphysical voids. Her voice is fractured, layered, and disembodied; it echoes across these voids, signalling a postcolonial condition of epistemic disinheritance. The camera’s languid pacing, disjointed voice-overs, and ambient soundscapes resist narrative logic. Rather than offering a coherent or redemptive story, Naked Reality performs disorientation, presenting its grotesque form as a cinematic language of loss and technological haunting.

Mignolo’s concept of epistemic disobedience again offers a powerful frame for understanding this refusal of clarity. In The Darker Side of Western Modernity, Mignolo critiques how colonialism imposed a universal system of knowledge grounded in Western rationality, linear time, and ontological coherence while rendering all other ways of knowing as irrational, primitive, or grotesque (Mignolo 2011). Naked Reality rejects these colonial terms of legibility. Its formal disruptions – glitching images, fragmented voice, temporal loops – become cinematic tactics of disobedience. The grotesque, in this sense, diverges from colonial epistemes altogether. It enacts what Mignolo calls a decolonial option, disrupting the grammar of perception itself.

In this speculative future, Africa is no longer a place but a simulation, a continent overwritten by techno-capitalism and global modernity. Wanita becomes a postcolonial cyborg, caught between machine and ancestor, history and oblivion. Her disembodiment is not merely technological but spiritual; her body a conduit for ancestral hauntings, her glitching presence a site of ontological resistance. She is not Man2, as Wynter would describe, but something else entirely: a fugitive figure who refuses assimilation into the Genre of Man.

Wanita’s spectrality, her defiance of becoming a coherent subject, challenges the epistemic violence that defines who counts as human. Her fragmented presence embodies Wynter’s call to imagine other genres of being; ones grounded in ancestral memory, ecological entanglement, and spiritual opacity rather than Enlightenment rationality (Wynter 2003). In Bekolo’s world, the grotesque is not an aberration but a strategy, a way to imagine survival after the severing of lineage, land, and language.

Ultimately, Naked Reality enacts grotesque aesthetics as a mode of epistemic insurgency. It does not clean up, explain, or resolve. Instead, it disturbs and disorientates, confronting viewers with the unresolved wounds of coloniality and the impossibility of return. The grotesque here is neither horror nor spectacle; it is survival in spectral form, a disobedient presence glitching at the edges of being.

Grief, in This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection, is not a private emotional event but a cosmological reckoning. Through the character of Mantoa, an elderly woman mourning the death of her last remaining family member, we witness a refusal not only of state-sponsored development, but of the entire epistemic system that renders land a commodity and mourning a linear process. Her grief is sacred, ancestral, and grotesque in its unwillingness to surrender. It transforms the body and landscape into contested zones where colonial modernity meets spiritual subversion.

The dam project that threatens Mantoa’s village is not simply a political manoeuvre but a continuation of the colonial imperative to extract, classify, and rationalise. Wynter reminds us that ‘Man’ as a colonial invention depends on the severing of human beings from their cosmological, ecological, and collective ways of life (Wynter 2003). Mantoa’s resistance to displacement is a negation of Man2’s logic that sees land as lifeless and grief as a problem to resolve. Her stillness, her rituals, her refusal to cooperate become a grotesque distortion of the colonial desire for order. She does not perform the ‘resilient’ widow; she becomes an interruption in time itself.

Saidiya Hartman’s work on mourning, loss and historical trauma centres on precisely this question. Hartman teaches us that the afterlives of slavery and, by extension, colonial violence, do not reside in spectacular scenes of suffering alone but in the quiet fractures of everyday life (Hartman 1997). Mantoa’s village is marked for disappearance, her ancestral ground slated for flooding. The land itself mourns. The grotesque emerges not through horror or chaos, but through atmosphere: extended silences, the staging of the body in a still tableau, and the flattening of narrative time. These gestures reflect Hartman’s resistance to reinscribe trauma through spectacle. They instead conjure an affective haunting, a mood of grief so thick it distorts temporality.

Visually, Burial draws heavily on formal stillness and symmetry, and scenes often resemble sacred paintings or funeral icons. The grotesqueness here lies not in dismantlement but in density. Every frame is heavy with memory. The camera rarely moves, but its gaze is unrelenting. The landscape is treated not as scenery but as a wounded archive. Dust, stone, and silence speak. This is a grotesque that demands reverence, a spiritual grotesque that refuses the rational choreography of progress, development, and resolution.

In her final act, Mantoa stages her own burial. This is not submission; it is cosmic dissent. She inserts herself into the land as protest, as spell, as myth. Her body becomes both a barrier and an offering, a grotesque monument against erasure. In this way, Burial answers both Hartman and Wynter, in that it imagines a genre of the human beyond coloniality, one that is rooted in the sacred, the non-linear, and the wounded terrain of history.

Radical lineages: Dada, Fluxus, and Feminism

Grotesque aesthetics in African cinema do not emerge in isolation. They resonate with the experimental ruptures of Dada and Fluxus, movements that rejected coherence, logic, and institutional control. Like Dada, grotesque cinema thrives on contradiction, fragmentation, and visual disobedience. Like Fluxus, it interrupts traditional boundaries between art and life, challenging the very expectations of form, narrative, and time.

But where the avant-garde operated within the aftermath of European crises, African grotesque cinema emerges from the still-active wreckage of colonial modernity. Its distortions are not abstract provocations; they are necessary responses to the enduring violence of racial capitalism, epistemic domination, and ontological erasure. In this context, grotesque rupture becomes politically urgent. It is not absurdity for its own sake, it is mourning, memory, and refusal rendered through dissonance.

This is where the grotesque breaks from its Western precedents. It is not a gesture of nihilism or anti-art, but a confrontation with colonial archives, developmentalist myths, and the rationalist logics of the Genre of Man. These films do not seek aesthetic innovation alone; they use aesthetic rupture to unravel what colonial modernity has deemed legible, human, and real.

In this sense, grotesque African cinema aligns more closely with practices that centre embodiment, historical injury, and survival. These aesthetics do not tidy the wound – they hold it open. They return to the viewer a world saturated with hauntings, where grief is not staged for sympathy but activated as protest. These are not simply formal strategies. They are methods of unknowing, designed to disturb the visual and temporal orders inherited from colonial frameworks.

The grotesque, across these films, is less a style than a stance. It insists that what is fractured should remain fractured. It refuses reconciliation, and instead invites a reconfiguration of the human that begins not with order but with rupture. Through these counter-cultural entanglements, grotesque aesthetics become a decolonial praxis: a method for destabilising colonial categories, reclaiming disfigured memory, and envisioning worlds beyond the limits of Man.

What remains when history refuses to resolve? When the archive breaks, when memory distorts, when the body refuses to perform as it’s told? Grotesque aesthetics do not look for answers. They linger in the cracks between grief and revolt, between what was and what might still be. These films do not offer redemption. What if the grotesque is not excess but inheritance? What if disfigurement is a language for those disfigured by history? Can rupture become a ritual? Can opacity be a kind of freedom?

Fragments of Refusal soundscape