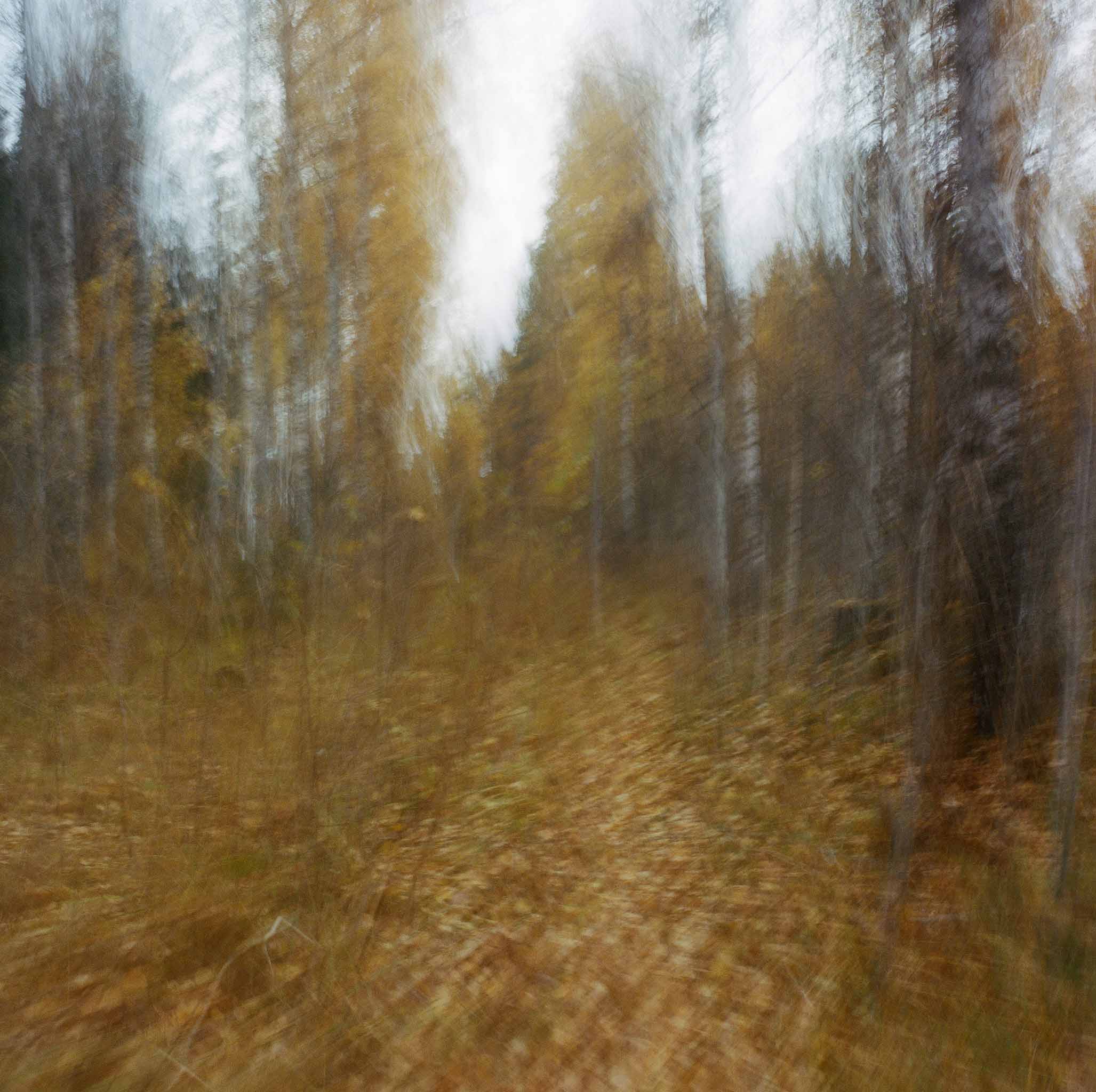

A gap is visible in the tree line, where the tracks were displaced fifty years ago. This passage between the two villages was disconnected by the border between nation-states. Now this trace of the railway points to nowhere. By following such a trace, one follows a fantasy.

The Introduction

However, the implications of the border are not limited to the representations conveyed by signs. For example, the urban theorist Neil Brenner and the geographer Stuart Elden have claimed that in addition to “territorial practices and representations of territory … territory also takes meaning through the everyday practices and lived experiences” (Brenner and Stuart 2009, p. 366). This claim corresponds with sensory observations we gathered during our numerous journeys with the Disconnected Space Research Group to the borderlands between Russia and Finland. Our observations demonstrated the unexpectedly complex experiential meanings which the border is capable of generating.

In this article, I aim to portray our research as an evolving process, where each journey yielded observations and prompted questions that, in turn, motivated and shaped the subsequent journeys. I call these journeys ‘stitches’, as if they stitched together those invisible roots in the landscape, which are absent but powerful. Photographer Hanna Koikkalainen, who joined this project in 2018, made several journeys to the site of our study, sometimes joining the rest of us, but also undertaking several journeys individually. In the article, our observations concerning our sense of the borderland are made in the space between images and texts.

The First Stitch: A Journey to the Borderland in Parikkala (Finland)

So, I entered the section of the ruined railway, located near the border in Finland, in March 2017. I walked from the Parikkala railway station towards the border, a distance of approximately nine km. This is how I remember it:

Spring was in the air. Patches of melting snow were visible here and there. My first impression of the site of the ruined railway line was that there were traces of a ski trail in place, where the tracks had been. Trees and plants grew on the railway embankment, where decaying sleepers jutted out from the snow.

As I reached the end of the field, the lane plunged into the forest. There was still a lot of snow in the shade of the trees, which made it hard to walk. Eventually, the railway line turned into a forest road. I came across an old whistle post, which confirmed that I was still following the railroad's lane. In proximity to the border, a road embankment ran across the tracks. Other than the barracks of border control, the houses nearby were abandoned.

On the other side of the road, the border region opened up into a field, across which the tracks' trace continued towards Russia. This is where I first noticed the surveillance cameras.

I arrived at the edge of the frontier zone. Without a permit, I could not go any further. Soon, a border guard approached, greeting me dispassionately. At that time, the frontier zone was only a couple of hundred metres wide from the edge of the border. Watching how the lane of the ruined railway continued, I dreamed about following footsteps.

My most vivid observation from the first journey was how, in one part, the absence of vegetation first defined the track’s trace, and then the presence of it. This destabilising characteristic of the trace, which was ultimately caused by the performativity of the border, began to fascinate me. I was also intrigued by the fact that the locals still used the railway as a pathway, which confirmed my initial assumption that, despite being in ruins, the railway still retained aspects of its original use.

Between 1948 and 1958, the railway line was used to transport war reparations from Finland to the Soviet Union, following which the line was disconnected entirely. The tracks on the Finnish side, amounting to nine kilometres, were dismantled in 1975 (Ahola 2012).

I also learned that the border crossing point, located close to the former Syväoro station, was established in 2001 and intended only for the transportation of goods..

In subsequent years, Parikkala municipality, along with its regional partners, campaigned to upgrade the border crossing from temporary to international (Kaskinen 2022, p. 51). At the time of my first journey, the slow process of normalising cross-border mobility seemed to be in progress.

The Second Stitch: The Journey to the Borderland in Russia

The photographer Hanna Koikkalainen had made many journeys to Russian Karelia. In 2018, I invited her to join me on a quest to visit the Russian side of the disused rail line. Soon, we learned that the thicket of regulations would resist our quest.

Finally, we were granted the necessary permits for the journey. However, they came with certain practical limitations. The border-crossing had to be done by car. The border zone permit allowed one to visit the zone only during the daytime, which meant that our 13-kilometre journey on foot through terrain whose difficulty we could not estimate, would need to be accomplished within about eight hours. So we set off on a foggy morning on 1 August 2019.

The border crossing itself was merely a formality, but on the other side, we faced a bureaucratic challenge. We were granted only a single border zone permit paper covering our whole group, but since we could not leave our cars in the border exclusion zone, our group had to be split. The convoy of cars took the document along with them, while the rest of us stayed at the perimeter of 400 metres from the border (as close as a civilian can get), and waited without a document. Soon, the patrolling border guard approached us and told us that we were not entitled to remain in the border zone. None of us spoke Russian, so we kindly refused and waited. After what seemed like a long and stressful wait, our convoy returned with the documents, and we were finally free to go.

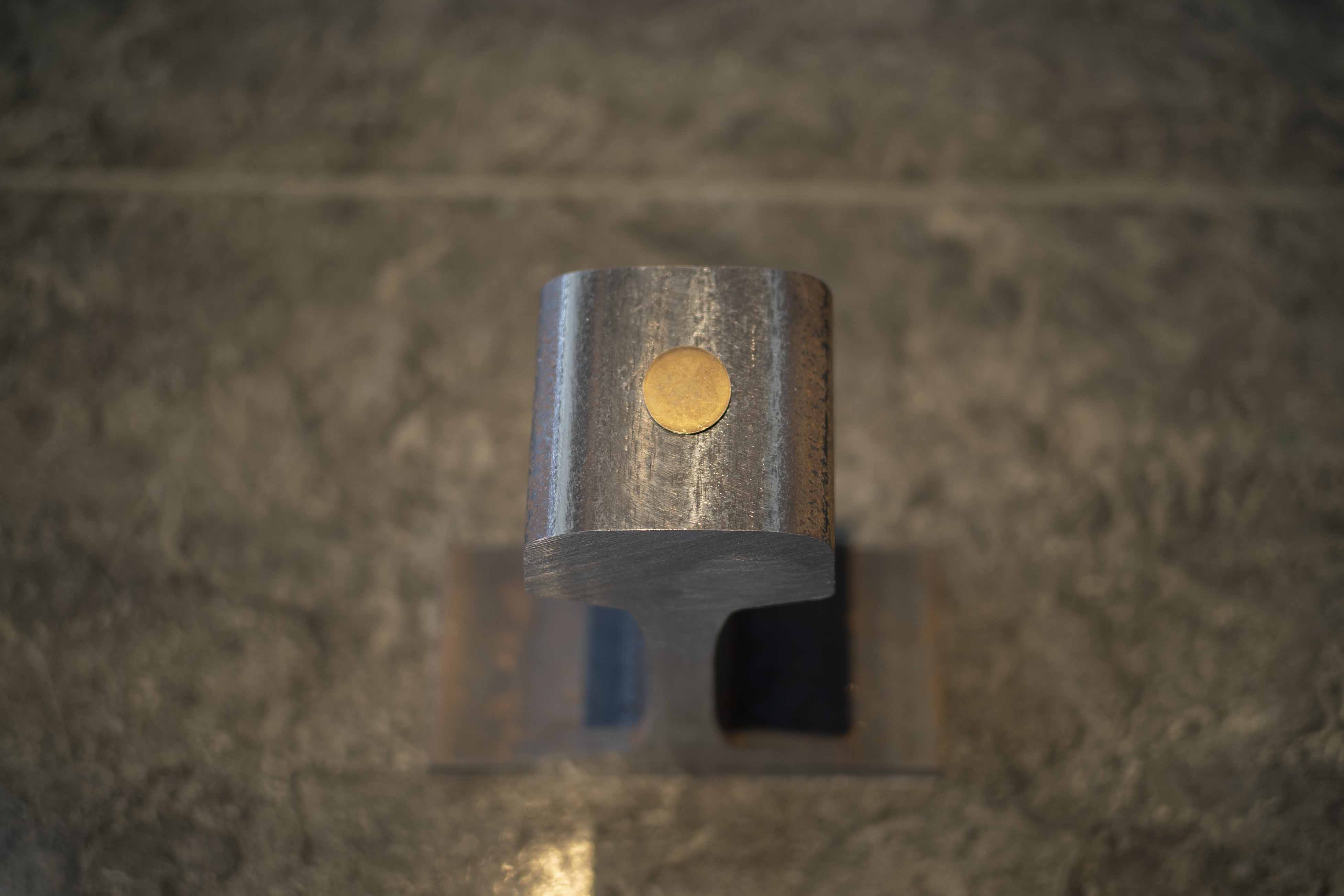

Then we arrived at Sorjo. The former station had been converted into a summer retreat, but no one was around. Further on, we met a collapsed railway bridge, and finally, as dusk fell, we found the point where the iron bars of the tracks were still in place. We were at the edge of the village of Elisenvaara.

We spent the next night on the floor of the municipal cultural and sports centre, which had kindly been offered to us by the local authorities. We were about to rest when the border control officer came to greet us and scolded us for violating the terms of our border zone permit. He checked our phones and wrote some code on them, which revealed the phones' telecom identification information, seemingly checking if we had stayed on the tracks. Then he left. From that point on, we knew we were likely under surveillance for the remainder of our stay in Russia.

Tracing the Past of the Border Exclusion Zone

The most remarkable observation of this journey was the vast difference between our sense of the borderland in Russia relative to our experience in Finland. In Finland, the borderland was actively used by civilians, and the sphere of restrictions was a narrow space next to the border. In Russia, however, the border marked a distinct periphery where human activity was conspicuous by its absence. The experience led me to study the history of the Russian border zone, and through this, I became familiar with the chain of events closely connected to Finland's history.

Initially, the border was porous, but paperless border crossings were criminalised by the Soviet Union in 1924, with the penalty being forced labour (Chandler 1998, p. 70). The OGBU, which governed both border mobility and forced labour camps, used the penalty as a means to accumulate a cheap workforce in its labour camps (Jänis-Isokangas 2024, p. 354). The establishment of the Border Exclusion Zone system followed in 1927. It consisted of various strips of land, starting four metres from the border and extending up to 22 kilometres from the border. The zones were subject to multiple restrictions concerning mobility (Chandler 1998, p. 63).

After the Second World War, which ended between Finland and the Soviet Union in 1944, the Soviet Union maintained a certain degree of ethnic discrimination. For example, the Allied Commission instructed the Finns to deport the Ingrian population to the Soviet Union. In the Soviet Union, they were forcibly exiled, and the exile lasted until 1954. (Reuter 2022, p. 94). In 1993, the border zones in Russia were renamed as border strips, and the area of restricted mobility shrank by five kilometres (Ryzhova 2020, p. 57). The border exclusion zones were, however, re-established in 2004 (Ibid.), a development that we encountered during our journey to the Russian borderland.

Nowadays, the conception of the border as an impenetrable barrier is not just a Russian policy. In 2001, the European Union adopted pre-border policies governing visa requirements, which effectively made it impossible for citizens of numerous nationalities to enter the European Union legally (Bueno Lacy and Houtum 2024, pp. 235–236). This was followed by the construction of fences at the borders of the European Union to block the influx of paperless migration (Ibid., p. 239). Finland began constructing a new border fence with Russia in February 2023. On 15 December 2023, Finland temporarily closed its border with Russia altogether. On 16 July 2024, a new bill for the Act on Measures to Combat Instrumentalised Migration was adopted (Ministry of the Interior, 16 July 2024). The blocking of migration was, after all, the reason behind the construction of the wall.

Turning Point

The coming of the fence was not in our sight when we completed our journey to the Russian side of the border. In the following autumn of 2019, the Finnish Government decided to upgrade the status of the border crossing in Parikkala to an international one, following Russia's initiative. The border crossing was scheduled to be operational in 2024. This gave a new urgency to our project. We planned new steps for the project, as it appeared that border policies might be changing. I conceived the idea of repeated participatory journeys to the site of the ruined railway. We would invite groups of Finnish and Russian writers, to whom the journeys to the borderland would become the subject of reciprocal correspondence.

Our plans were initially interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which resulted in the blockade of the border and a halt to collective cultural activities. Just when the restrictions concerning the border crossings were about to ease in the winter of 2022, Russia began a new invasion of Ukraine. To collaborate with the Russian artists and writers became problematic. We did not want to collaborate with those who supported the war. For those opposed to the war, our project, which would have involved dealings with the FSB, became a risk. The significance of the border had changed.

For us and for those Russians like Mikhail, who resisted the regime, the other side of the border became unattainable, a non-place. I contacted Mikhail and invited him to our Disconnected Space Research Group. We took a trip to the abandoned railway tracks in Parikkala. Together, we began planning a performance to be held on the Finnish side of the border, which would invite Russians and Finns to dream of alternative futures.

The Performance in the Form of Letters

Our performance took the form of a solitary walk that followed the trace of the ruined railway line, from the village of Parikkala to the edge of the border zone in the vicinity of the Finnish-Russian border. On the way, participants were guided towards several letters that introduced the reader to various imaginary plays. The letters dealt with the theme of defection, as well as the interplay between the present and the absent. Our performance included nine letters, with the final one requesting participants to write a travelogue of their experiences.

Our project had two parts. First, we invited Russians stationed in Finland to participate. Ultimately, we made two such trips. In the second phase, we asked the locals of Parikkala to participate.

The Third Stitch: A Journey Across a Dark and Cold Landscape in 2022

The first performance took place on November 26, 2022. Sergei had just arrived in Finland in search of asylum and participated, along with Mikhail and Pavel Rotts, an Ingrian Finn with Russian nationality, and a member of our Disconnected Space Research Group. We arrived in Parikkala in the early afternoon. The temperature was -5°C. The sun would set in two hours, so the journey across the borderland took place at dusk.

The reason why every participant's letter addressed the relationship between father and son was partly due to a letter in which I described my dream of speaking with my recently deceased father. Additionally, the war in Ukraine was justified with patriotic reasoning, which subjectivised the gender of men in a specific manner.

The Fourth Stitch: A Journey Across a Snowstorm in 2023

The second performance took place on February 18, 2023. This time, two women of Russian origin were invited, Anastasia Artemeva and Adel Kim. Anastasia is an artist who has lived in Finland for a long time. Adel had recently arrived in Finland to work on a research project examining the experiences of Finland and Russia in relation to the role of artistic residencies in sustainability.

This time, the journey took place in a snowstorm. It wasn’t as dark as in November, but the intense snowfall limited visibility, and created thick piles of snow here and there. Anastasia was skilled at skiing and more familiar with the conditions, but Adel was wearing snowshoes for the first time. By the end of the journey, she was visibly exhausted.

Adel’s letter was presumably addressed to her mother. In it, she compares her walk to previous experiences of confronting her physical limits. Her letter reflects feelings such as being lost, feeling cold, and being exhausted. Reading her letter afterwards, I am ashamed of my insensitivity for not taking into account her different background concerning the physical conditions she faced.

She also writes about her mixed ethnicity, which she sees as both a gift and a curse. Having moved so often, the notion of a sense of belonging has lost its meaning for her. According to the letter, this makes her feel like an outsider, yet at the same time gives her freedom.

Anastasia wrote two letters. One was crafted from various scraps of clothing, and appears to be a reflection on the sensorial perceptions and sensations of the journey. The second was addressed to “Scream” and written in a poetic and polemic style. It contains fragmentary observations of nature, such as the sound of a woodpecker, combined with dreamlike thoughts and critical reflections on the situation in Russia. She compares her situation with wolves that “wander here and there without a passport”.

Stitches Come Together

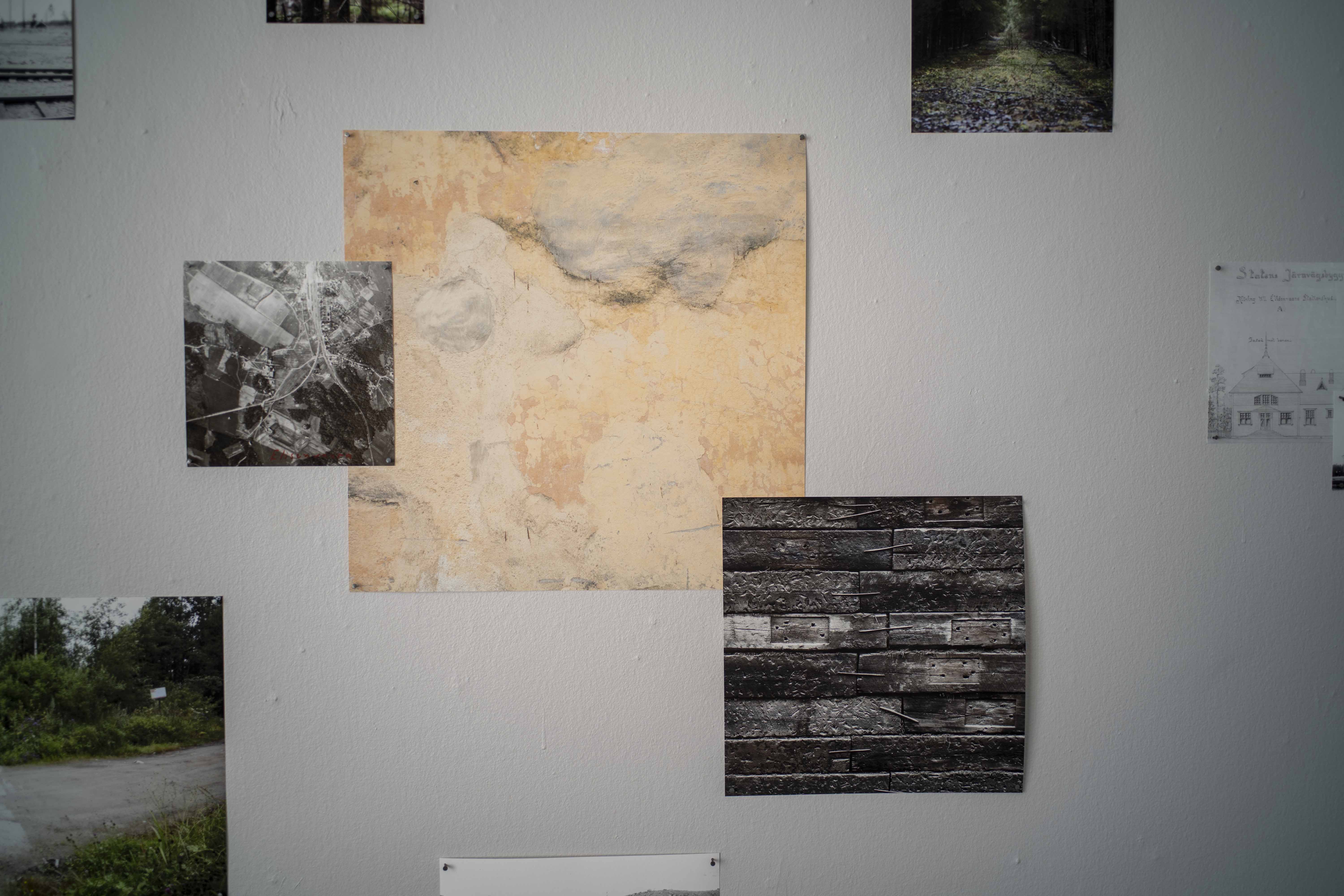

Our site-specific performance, including all the letters produced as a result, became part of the installation by the Disconnected Space Research Group at the M_itä Biennial, held in the city of Joensuu, running from May 13 to September 17, 2023. The contemporary art biennial, organised by the art museums of Joensuu, Kuopio, and Mikkeli, invited artists to critically engage with the history, traditions and complex socio-political conditions that have shaped the region of Eastern Finland.

The letters from Adel, Anastasia, Mikhail, Pavel, Sergei as well as the letters written for the performance, were placed on small tables. The tables were covered with glass plates, which reflected Hanna’s photos on the walls.

The installation made use of documentation in two ways. In one sense, our documentation referred to times, places and events taking place elsewhere. As a constellation however, these elements gained new meaning. Hanna Koikkalainen’s documentary photos, the letters and the pieces of tracks cut by Pavel Rotts, worked together to refer to events that took place in other places and times. They mirrored their points of reference.

According to Boris Groys, the introduction of documentation as a work of art produces the condition in which the subject of documentation “becomes a life form”, and the artwork itself “becomes non-art, a mere documentation of this life form”. (Groys 2008, p. 53).

However, Groys also reminds us that, in the context of an exhibition, a document as an artwork “gains a site–here and now as the historical event” and thus becomes alive in the installation (ibid., p. 64). Our installation executed a similar two-directional movement. In one sense, our documentation, including Hanna’s photos and the letters by Adel, Anastasia, Sergei and Mikhail, was based on our authentic journeys. These observations however, were given meaning by the setting of our installation.

This two-directional act of displacement was crystallised in the use of written letters in the installation. Those letters, originally written as private messages from one person to another, gained their true meaning elsewhere — in another time, through the correspondence between the writers. And yet there they were, on display for the public. In that moment, they took on a new meaning through the act of strangers reading them.

Conclusions

Stitching Tracks became an unsystematic study of the borderland as a spatial experience. This was partly due to our artistic approach to the subject, but the characteristics of the borderland also played a role. Within the time-frame of our study, the concept of the border underwent significant changes. This came as a surprise to most of the world.

Our project followed the performative paradigm of research, which, according to the theorist of artistic research Barbara Bolt, is characterised by repetition with difference (Bolt 2016). We conducted iterative walks across the ruined railway line, with each trip yielding new insights about the site of our study. In the turbulent period of our project, each journey exposed the site in a singular way. The myriad of experiences related to spatial disconnection and the performativity of the border, that is, the act of bordering. The disconnection was, however, not complete, since the site of our study was experientially also linked to those associations that preceded the disconnection.

Nowadays, disused railway lines serve as a growing medium for plants and other natural species.

Despite their redundancy, they still communicate with us as a trace. This can be understood in one sense as the trace of a railway, but also as a reference to the performativity of the border. In attempting to understand its unspoken message, interpretation arises through sensory perception. In his famous essay "Signature Event Context" (1971), Derrida notes that, if we consider writing as a means of communication, it entails the disappearance of the receiver of the message (Derrida 1988, p. 7). Writing continues to produce effects independently of its original context (Ibid., p. 5), and in the rupture of present references (Ibid., pp. 9–10). The landscape of the ruined railway lends itself to a spatial interpretation of this theoretical reflection.

Moreover, this landscape invited us to explore the form of a private letter as an artistic method. We also found it to be a tactic for resisting the disruptive power of the border. The letters from 1932, which employed misleading expressions, such as “berry-picking”, to deceive the censors, can be studied from this perspective. Ann Goldberg, a scholar of Modern German studies, has conducted a more precise analysis of the tactics employed by private individuals to deceive censors in civilian correspondence between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany (Goldberg 2006, pp. 166–167). For our project, the letters were taken out of their original context, leaving the receiver of the message with puzzling gaps and questions about the relativity of the text. However, if we follow Derrida’s thinking, the writing in the letter maintains its performativity even in the complete absence of its original context. In our performances, we utilised the letter form to harness this creative potential, with unfounded dreams about the possibility of change.

The stage for those possibilities was set by the borderland, where the experience of space is shaped by the absence of the agents, contexts and intentions that once shaped the landscape. This ambiguous absence greatly impacted our experience of the borderlands.